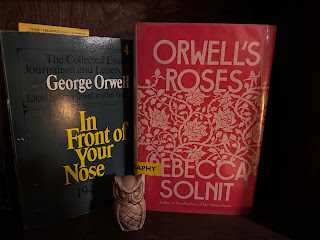

That's the opening line of Rebecca Solnit's most recent book Orwell's Roses, and the writer-slash-gardener is George Orwell. Orwell wrote about the roses (and also the fruit trees and gooseberries he planted) in his essay 'A Good Word for the Vicar of Bray' of 1946. Solnit calls it 'a triumph of meandering that begins by describing a yew tree in a Berkshire churchyard.' It takes one to know one: Solnit is a champion of the meandering essay herself."In the spring of 1936, a writer planted roses."

And this is law, I will maintain,Until my Dying Day, sir,That whatsoever King may reign,I will be the Vicar of Bray, sir!

Still, the Vicar planted that yew tree. Orwell:

"An oak or a beech may live for hundreds of years and be a pleasure to thousands or tens of thousands of people before it is finally sawn up into timber. I am not suggesting that one can discharge all all one's obligations towards society by means of a private re-afforestation scheme. Still, it might not be a bad idea, every time you commit an antisocial act, to make a note of it in your diary, and then, at an appropriate season, push an acorn into the ground."

Or roses.

Solnit was in England for a book tour and was interested to see what was left of Orwell's plantings. Only the roses survived.

"There are many biographies of Orwell, and they've served me well for this book, which is not an addition to that shelf. It is instead a series of forays from one starting point, that gesture whereby one writer planted several roses. As such, it's a book about roses..."

An interesting topic for a meander.

So many fascinating things: Emma Goldman, the photographer Tina Modotti, Stalin and lemon trees. Columbia is the source for 90% of North America's commercial cut roses and is infamous for its terrible labor practices. Solnit manages to visit a rose farm there. It's not a long book, but it's fascinating and I won't even try to tell you all the things in it.

One of her main themes is the frequent puritanism of the left. Orwell is sometimes absorbed into this. Is he a dour political writer who can only tell us the terrible things are going to happen, the terrible things that are happening? Maybe not just. Turns out nature is important in 1984 and is written about well. This leads her to Emma Goldman, the anarchist, and Tina Modotti, the photographer and Communist.

It is also about what a political essayist can and should do: in Solnit's case in this book, feminism, labor issues, the creeping return of totalitarianism, climate change.

Pretty great stuff. It's the fourth I've read of her twenty-five or so books. (River of Shadows, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, The Faraway Nearby and now this.) Right now it's my favorite, and is likely to stay so at least until I read the next one.

"Orwell's signal achievement was to name and describe as no one else had the way that totalitarianism was a threat not just to liberty and human rights but to language and consciousness, and he did it in so compelling a way that his last book casts a shadow--or a beacon's light--into the present. But the achievement is enriched and deepened by the commitment and idealism that fueled it, the things he valued and desired, and his valuation of desire itself, and pleasure and joy, and his recognition that these can be forces of opposition to the authoritarian state and its soul-destroying intrusions.The work he did is everyone's job now. It always was."

Another new-to-me author. I'll have to check out one of her books sometimes.

ReplyDeleteShe's pretty good. I think she's responsible for the work mansplaining, but I haven't actually read that essay.

Delete