Friday, June 30, 2023

Andrew Greeley's Happy Are The Clean Of Heart

Thursday, June 29, 2023

Rubaiyat of Jahan Malek Khatun

Four Rubaiyat

I feel so heartsick. Should my doctor hear,He'll sigh and groan and want to interfere;Come on now dearest, heal me, you know howTo make my doctor's headache disappear.You wandered through my garden, naked and alone(The roses blenched to see their beauty overthrown).My cheeky love, your body is the Fount of Youth(But in your silver breast your heart is like a stone).

I swore I'd never look at him again,I'd be a Sufi, deaf to sin's temptations;I saw my nature wouldn't stand for it--From now on I renounce renunciations.

The roses have all gone; "Goodbye," we say; we must;And I shall leave the busy world one day; I must.My little room, my books, my love, my sips of wine--All these are dear to me; they'll pass away; they must.

-Jahan Malek Khatun (tr. Dick Davis)

These were among the rubaiyat that sent me back last week to reread the ones by Omar Khayyam and translated into English by Edward FitzGerald. They're by Jahan Malek Khatun (1324-1393, approximately). She was the niece of Abu Ishaq, the Injuid king of the area around Shiraz in what is now southwest Iran, at least until his overthrow in 1353.

The ruba'i is a four-line form that rhymes AABA. The third one quoted is thus technically not a ruba'i, and either Khatun or Dick Davis the translator is being a little slack. I didn't mind... 😉

Sunday, June 25, 2023

Sunday Salon

|

| The Salonnière invites you... |

Books

I read Harini Nagendra's first mystery The Bangalore Detectives Club. Pretty fun! The characters were charming (except for the villains, of course...) and the setting was fascinating: 1920s Bangalore (Bangaluru). I'll read the next when my library gets it. (They're on order.)Earlier this week on the blog a review of Eleanor Catton's Birnam Wood. Enjoyable, though I still prefer The Luminaries.

A selection of rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam in the famous translation of Edward FitzGerald.

And another mystery, the classic The Daughter of Time by Josephine Tey.

On The Stack

Let's take it from the top. That's:

Billy the Bunny.

Happy are the Clean of Heart, a Fr. Blackie Ryan mystery that I started while I had to wait around somewhere and should finish soon.

John McGahern's Amongst Women. A book I was going to read before our trip to Ireland, but it didn't get here in time. It's supposed to be a classic and so far I kind of think it is.

No progress whatsoever on James Baldwin's Notes of a Native Son... 😉

But some progress on Barbara Hamby's On The Street of Divine Love.

The library also delivered Georgi Gospodinov's Time Shelter. It won the Booker International this year and there's no way I'll be able to renew it, so it needs to happen in the next couple of weeks. I've liked the others by him I've read. That will be Bulgaria for this year's European Reading Challenge.

Foody

It's strawberry season here!

How was your week?

Friday, June 23, 2023

Eleanor Catton's Birnam Wood

But that's not all it is."Birnam Wood was defined in carefully apolitical language as a grassroots community initiative that planted sustainable organic gardens in neglected spaces and featured a commitment to help those in need."

Mira Bunting is the founder and main figure of Birnam Wood, a guerrilla gardening collective in New Zealand. Four years ago, the emphasis was on the guerrilla: anti-capitalist, rebellious. Now most of their vegetable plots are planted with the agreement of the owners, and the produce is shared out.

Part of the reason for the practicality is Shelley Noakes. Shelley rather worships Mira, but also is beginning to feel used, and at the very start of the novel she decides to sleep with Tony Gallos, Mira's ex-one-night-stand as a way to assert her independence. Tony's just appeared on the scene after teaching in Mexico for four years, and Shelley knows perfectly well Mira and Tony have unresolved issues.

Meanwhile there's been an earthquake in the Korowai National Park that killed five people and blocked a major road. This means that an old farm at 1606 Korowai Pass Road is now isolated. It's owned by Owen Darvish and his wife Lucy, and he's just been knighted for services to conservation even though he's the owner of a pest control company. (One of the things he kills is invasive species.) Mira thinks here is the grand coup that Birnam Wood needs: guerrilla gardening on the Darvish estate. Birnam Wood will go to Dunsinane. (1606 is likely the year in which Shakespeare's MacBeth was first performed.)

But one other figure has seen possibilities near Korowai National Park; that's Robert Lemoine, an American billionaire. His money is from a drone startup, but he envisions a different sort of financial coup in New Zealand.

That's our major players lined up. The first two-thirds of the novel is getting to know them, individually and in relation to one another; the last third is quite the thriller as their different goals conflict and their unknowing about each other gets resolved. The conflict is political and environmental.

The novel's at times funny. When I saw Eleanor Catton here a couple of months ago, she read from a passage with one of Tony Gallos' rather over-the-top rants. The audience--the book was brand-new at that point, and almost nobody had read it--were first absorbed in Tony's righteous anger, then laughed nervously, then laughed out loud. Catton can pull that sort of thing off.

Tony's still kind of a hero, even if he only has the vaguest sense of reality, and the book ends with him:

"...so that somebody would see it, so that somebody would notice, so that somebody would care, and as the fire began to blaze and crackle up the ancient trees around him, Tony prayed that somebody would come to put it out."

So a pretty fun novel with some serious themes. I did, however, feel that the American billionaire drifted in from a different sort of novel (or film), likely one involving James Bond. I would also say I still think The Luminaries is the one to read. (Though I haven't read her first, The Rehearsal).

Another book actually from my 20 Books of Summer list!

And, as it turns out, it's my first Big Book of Summer. When I signed up for the challenge, I didn't have a copy of the book in hand and didn't realize, but as it turns out it's 432 pages and so qualifies. I still hope to read a few other monsters. Thanks to Sue and Cathy for hosting!

Thursday, June 22, 2023

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

[Selections]

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread--and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness--

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!And lately, by the Tavern Door agape,Came shining through the Dusk an Angel ShapeBearing a Vessel on his Shoulder, andHe bid me taste of it; and 'twas--the Grape!One Moment in Annihilation's WasteOne Moment, of the Well of Life to taste--The Stars are setting and the CaravanStarts for the Dawn of Nothing--Oh, make haste!The Moving Finger writes, and, having writ,Moves on; nor all your Piety nor WitShall lure it back to cancel half a Line,Nor all your Tears wash out a Word of it.

Tuesday, June 20, 2023

Josephine Tey's The Daughter of Time

"Truth is the daughter of time."

-Old proverb

Sunday, June 18, 2023

Sunday Salon

|

| One last salon-ish Ireland photo |

On the Blog

Diligent week on the blog. I wrote up Cousin Bette, a book from my Classics Club list. Then I posted a Barbara Hamby poem I like, and last Biography of X, from my 20 Books of Summer list, which was OK, but I didn't like it as well as I hoped I would.

I also finished Josephine Tey's classic mystery The Daughter of Time, which I should write up soon.

On the Stack

The library delivered Eleanor Catton's Birnam Wood much faster than I thought it would. It's still popular and I'll have to read it soon. The same is true of The Bangalore Detectives Club by Harini Nagendra.

I think my next Classics Club book will be James Baldwin's Notes of a Native Son. And I continue to make my way through Barbara Hamby's book of poetry.

Foody

It's asparagus season here! One of our favourite uses:

I first came across the idea of shaved asparagus pizza at Smitten Kitchen, but I've fancied it up a bit. She uses just cheese for the base, but I now do a garlic cream sauce. You see I've added some diced salami on half (for thems whats wants it... 😉). A slice of prosciutto works, too. To go all in, some shaved truffle pecorino is a treat, but that requires a trip to a special cheese store for me, and I didn't get there last week...

Hope you all had a great week!

Friday, June 16, 2023

Catherine Lacey's Biography of X

"She said--'He didn't put anything in the paintings because he doesn't know how. He doesn't know anything about art, and worse, he doesn't care.' Now, of course I was accustomed to criticism--I even welcomed it on occasion--but no one's opinion ever made me as doubtful as hers." [p.240]

Thursday, June 15, 2023

17 Dollars

17 Dollars

That's how much the man who owned DuBey's gave mefor my books that time you insistedthey were taking up space and we needed the money.We were poor, sure--you a painter,me a student--but 17 dollars? I remember looking at it--a ten, a five, and two ones--and thinkinghow little it was compared to the cardboard boxyou'd lugged into the store that afternoon,all the days and nights those people--Russian aristocrats,English ladies, Southern dingbats, Irish wild men--taught me how to be human: flawed, yes, but with aspirationsof divinity. Where were Prince Myshkin,Dorothea Brooke, Hazel Motes, Stephen Dedalus?We could maybe buy groceries for a weekor go to the café down the street for dinner or lunch,but how could I get by without my Borgesor Wuthering Heights? When I think back on that day,that's when my heart hardened in my chestlike a walnut gone bad, so when another mantold me he loved me, I looked at himand didn't ask myself would he love me foreverbut would he love my piles of books.When they began to grow by the bed, teeter on every table,and topple to the floor, would his mouthbecome thin and his voice rise like an accountant'swith a ledger? I handed you the moneyand walked away. You ran to catch up,said, "We can take it back," but I feltlike the poor mother who has given her childto the rich couple because they can buy herfrilly dresses, give her piano lessons, send her to fancy schools.I couldn't take care of my Jane Eyre,Molly Bloom, Anna Karenina, but maybe some else could.Even now I go to the shelves to look for The Trialor The Day of the Locusts or Thus Spake Zarathustra,and when I can't find them, I knowthey were in that box. What did we do after? Walk home,eat dinner at the cheap Chinese place,where you picked the shrimp out of the eggrolls and asked,"Is that pork? It tastes like pork." Latera French couple bought the building, ripped out the red silkdragons, the lanterns with gold tasselsand turned it into the bistro my new husband and I went tomost weekends when we were first married,where I learned to drink wine, eat escargots and bitter greens.Now it's the parking lot of the federal courthouse,and I can't drink red wine without sneezing. Why did I keepThe Manifestos of Surrealism, which I haven't openedin thirty years? Where are The Moviegoer, Nightwood,Tender Buttons, Wise Blood? Years later,both married to other people, you said you were sorryfor making me sell those books. We were standing outsideyour studio in Chicago. It was summer and you were holdingyour daughter's hand, and I said it was nothing,but even that day long ago I knew it was everything and it was.

Tuesday, June 13, 2023

Balzac's Cousin Bette

"I am a man of my time; I respect money."

It's a dark story, but not all is dark. Balzac strikes me as capable of anger, and if you can get angry, it's because you think things could be better. Hulot does a lot of damage in his quest for money for his mistresses, but that ugly quest for money is representative of his time. At one point, needing two hundred thousand francs, here's Hulot, sending Adeline's uncle to Algeria as quartermaster for the French occupation there, describing a plan to cheat both suppliers and consumers enough to acquire the needed amount:

"There is a great deal of fighting over the corn, and no one ever knows exactly how much each party has stolen from the other. There is not time in the open field to measure the corn as we do in the Paris market, or the hay as it sold in the Rue d'Enfer. The Arab chiefs, like our Spahis, prefer hard cash, and sell the plunder at a very low price. The Commissariat needs a fixed quantity, and must have it. It winks at exorbitant prices calculated on the difficulty of procuring food, and the dangers to which every form of transport is exposed. That is Algiers from the army contractor's point of view."It is a muddle tempered by the ink-bottle, like every incipient government. We shall not see our through it for another ten years [Ed. note: it took a little longer than that]--we who have to do the governing, but private enterprise has sharp eyes. -- So I am sending you there to make a fortune..."

"Is there a man among you who ever loved a woman--a woman beneath him--enough to squander his fortune and his children's, to sacrifice his future and blight his past, to risk going to the hulks for robbing the Government, to kill an uncle and a brother, to let his eyes be so effectively blinded that he did not even perceive that it was done to hinder his seeing the abyss into which, as a crowning jest, he was being driven?...I never but once even saw the phenomenon I have described. It was...that poor Baron Hulot."

"Dessert was on the table, the odious dessert of April."

It was such a weird thing that I went and looked up the French (the Other Reader's copy shown above--I did NOT read it in French). Here's the French:

"Le dessert, cet affreux dessert du mois d'Avril."

Waring's translation seems reasonable. (Awful or atrocious says WordReference.com for affreux) What the heck is an odious dessert? It's probably early for berries in Paris in April, but, hey, who'd object to a nice gateau? I'm personally of the opinion that no dessert is odious. 😉

This was my spin book, and here I am blogging about it on the day the next spin is announced. Ouch! I was doing pretty well, but then Covid stopped me from reading anything serious for a bit, then I had some library books I wanted to read so I could return them, and by then I thought I'd better start over again. So here we are a month and a bit late...still it's another book off my Classics Club list, and a good one at that.

Sunday, June 11, 2023

Sunday Salon (Toronto's Doors Open)

|

| St. Lawrence Hall, Toronto |

Books

|

| Array Space, now home for electronic music |

|

| HMCS York, the Canadian Naval Reserve base in Toronto |

|

| The captain was there to show people around |

|

| Ornge [sic] emergency transport helicopter at Billy Bishop Airport |

|

| The airport fire station. These would not actually fit me, but they were popular. |

|

| Skyline view from the airport, which is on an island in the harbour. |

|

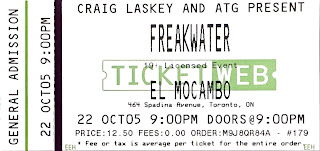

| El Mocambo or El Mo. The sign looks like the original, but was remade. |

|

| The rebuilt stage. The old sign was saved, but moved inside. |

|

| Photo of the Rolling Stones at El Mo. El Mo's a bit touting their glory days, but don't we all... |

|

| And I may have spent some time there myself back in the day. Just not with Sir Mick... |

Thursday, June 1, 2023

Hafez (Wine, Boys, and Song)

My Love Has Sent No Letter

My love has sent no letter forA long time now--I've heardNo salutations from him, noInquiries, not one word;I've written him a hundred times,But that hard-riding kingHas sent no emissary back,No message, not a thing!I'm wild with waiting, crazy, butHe's sent no envoy here--No strutting partridge has turned up,No graceful, skittish deer.He knows my heart must now be likeA fluttering bird, but heHas yet to send one sinuous lineTo lure and capture me.Damn him, that sweet-lipped serving boyKnows very well that INeed wine now, but he pours me noneAlthough my glass is dry.How much I boasted of his favors,The kindnesses we share--And now I've no idea at allOf how he is, or where.But this is no surprise, Hafez;Calm yourself, and behave!A king can't be expected toWrite letters to a slave.