The Case Of The Rolling Bones is a Perry Mason mystery of 1939. I use 'a' deliberately. Though I didn't actually check, I doubt it was the only one. Are Gardner's books the only ones that also give the month as well as the year of publication? He may be one of the few authors that needs it. For what it's worth, this was Gardner's book of September, 1939. (An otherwise ominous month.) It was *probably* the only one that month...

On the whole it was a medium good entry. Alden Leeds is an elderly man with a somewhat mysterious past who struck it rich in an Alaska gold rush in 1906. He's unmarried and the rest of his family likes it that way. Then he takes it into his head to marry a girl he knew from a dance hall back in Alaska--she's younger than he is, but not young--and the family decides, conveniently, he must be crazy. It's this that brings Perry into the case.

Leeds is also being blackmailed over that mysterious past and it's the blackmailer who gets killed. And Leeds is the prime suspect, and it's up to Perry to get him off.

There was some reasonably well-done fair-play cluing in this one, which is not a thing I usually associate with Gardner's mysteries. And the old coot quotient was high in this and they were amusing. It's Gardner and I could hunt up examples of slapdash construction, but if you know the Perry Mason series at all you wouldn't be surprised. Enjoyable.

That's very definitely the 1969 version not the 1939 model on my cover, but either way she's a:

Brunette. Golden Age. My Reader's Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt

Sunday, December 31, 2017

Saturday, December 30, 2017

Terry Pratchett's Hogfather

Hogfather is Terry Pratchett's statement of Christmas spirit. Pratchett is rather a sentimental satirist, and while in this he's making fun of many of the accompaniments of Christmas that message of Peace (and a little benevolent chaos) on Earth and Goodwill to All is a thing he will want to affirm.

The basic setup is this: the Hogfather is the book's stand-in for Santa Claus and somebody wants to murder him. They hire an Assassin to do the job. How do you murder a myth, assuming the Hogfather is a myth? Well, you get people to quit believing. So somebody has to act the part of the Hogfather/Santa Claus character, convincing the children he does exist, until the case can be unraveled, and the spreader of skepticism and cynicism discovered. Then the children can go back to their belief.

The someone who decides to act the part of the Hogfather is Death, a recurring character in the Pratchett Discworld universe. His granddaughter, with various helpers, tracks down the assassin and reveals the plot. They succeed, and the Hogswatch holiday is saved.

I thought this was a relatively weak entry in the Discworld series and that was sad, because Pratchett's Death is one of my favorite characters in the series. The plot in this was too complicated, with mysterious tangents to it. We see very little of the Assassin's interaction with Christmas things and far more with the Tooth Fairy. I'm not entirely sure why that happened.

Also, while I don't usually assign too much import to the old MFA bromide "Show, Don't Tell," it could have been applied here. One of the best things about the character Death is his desire to give up the scythe and long black robe and live a more normal existence. He's curious about human lives, but has this, umm, well-defined relationship with humans that keeps getting in the way. In previous books in the series, this provides a number of comic situations. But here we kept being told about Death's characteristics, mostly by his granddaughter, rather than seeing them in their funny excesses.

Anywho...amusing enough, but I had higher hopes.

The basic setup is this: the Hogfather is the book's stand-in for Santa Claus and somebody wants to murder him. They hire an Assassin to do the job. How do you murder a myth, assuming the Hogfather is a myth? Well, you get people to quit believing. So somebody has to act the part of the Hogfather/Santa Claus character, convincing the children he does exist, until the case can be unraveled, and the spreader of skepticism and cynicism discovered. Then the children can go back to their belief.

The someone who decides to act the part of the Hogfather is Death, a recurring character in the Pratchett Discworld universe. His granddaughter, with various helpers, tracks down the assassin and reveals the plot. They succeed, and the Hogswatch holiday is saved.

I thought this was a relatively weak entry in the Discworld series and that was sad, because Pratchett's Death is one of my favorite characters in the series. The plot in this was too complicated, with mysterious tangents to it. We see very little of the Assassin's interaction with Christmas things and far more with the Tooth Fairy. I'm not entirely sure why that happened.

Also, while I don't usually assign too much import to the old MFA bromide "Show, Don't Tell," it could have been applied here. One of the best things about the character Death is his desire to give up the scythe and long black robe and live a more normal existence. He's curious about human lives, but has this, umm, well-defined relationship with humans that keeps getting in the way. In previous books in the series, this provides a number of comic situations. But here we kept being told about Death's characteristics, mostly by his granddaughter, rather than seeing them in their funny excesses.

Anywho...amusing enough, but I had higher hopes.

Friday, December 29, 2017

Book Beginning: Randal Graham's Beforelife

Ian died at midnight on a Tuesday. Or maybe Wednesday. He couldn't be sure which, come to think of it, and now that he was dead the point seemed moot.

...is the beginning of Randal Graham's Beforelife.

Beforelife is the debut novel of Canadian lawyer Randal Graham, and as such it comes free of expectations. Well, there's a description on the back cover, which I did read--the novel takes place in an afterworld, more heavenly than George Saunders' Lincoln In The Bardo, but still not quite heaven enough for Ian. I think the opening isn't bad, with some humor and a bit unexpected, though it does depend on the fact that we know stories like this: Saunders, say, or Our Town. Anybody have any thoughts?

Book Beginnings on Fridays is a bookish meme hosted by Gilion at Rose City Reader. To play, quote the beginning of the book you're currently reading, give the author and title, and any thoughts if you like. Happy New Year!

Saturday, December 23, 2017

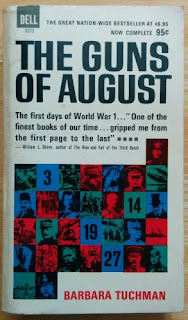

Barbara Tuchman's The Guns of August

The Guns of August (1962) is Barbara Tuchman's history of the opening of World War I. The first ninety or so pages in my edition of just under 500 pages are devoted to the situation in the main combatant countries in the years before the war. The rest of the book is devoted to the first month of combat and mainly to that on the Western front. The book ends with the end of August, 1914. The German assault on France has failed to take Paris or to destroy the French army, and the war will now settle down into the trenches in which the bulk of it was fought.

Basically Barbara Tuchman covered the militarily exciting bits and then stopped.

But that first month was exciting and Tuchman does an impressive job with it. It's touch and go whether the Germans would capture Paris and knock out the French in their opening push, and while we know the outcome, both sides were uncertain until the last minute.

Tuchman has clear favorites--she's an Anglophile and clearly likes Generalissimo Joffre of the French--but her irony undercuts and complicates her favoritism, especially in the battle scenes. Of one British officer, she writes: "...with that marvelous incapacity to admit error that was to make him ultimately a Field Marshal." She's good on the fog of war, the incapacity to make happen what you intend, to even understand what is happening. "Arguments can always be found to turn desire into policy," she writes of the German navy, but it could very well serve as a catchphrase of the book.

I do wish my edition had better maps; I'm reading the one that looks like that above, the paperback printing from the sixties. There are maps, but they're grainy and hard to make sense of. I also wish she'd done more with Austria-Hungary, which, after all, is where the war actually started. I'd recommend Christopher Clark's The Sleepwalkers on the opening of the war before battle, who's also very good and more sympathetic to Austria-Hungary's situation.

But very good indeed.

Basically Barbara Tuchman covered the militarily exciting bits and then stopped.

But that first month was exciting and Tuchman does an impressive job with it. It's touch and go whether the Germans would capture Paris and knock out the French in their opening push, and while we know the outcome, both sides were uncertain until the last minute.

Tuchman has clear favorites--she's an Anglophile and clearly likes Generalissimo Joffre of the French--but her irony undercuts and complicates her favoritism, especially in the battle scenes. Of one British officer, she writes: "...with that marvelous incapacity to admit error that was to make him ultimately a Field Marshal." She's good on the fog of war, the incapacity to make happen what you intend, to even understand what is happening. "Arguments can always be found to turn desire into policy," she writes of the German navy, but it could very well serve as a catchphrase of the book.

I do wish my edition had better maps; I'm reading the one that looks like that above, the paperback printing from the sixties. There are maps, but they're grainy and hard to make sense of. I also wish she'd done more with Austria-Hungary, which, after all, is where the war actually started. I'd recommend Christopher Clark's The Sleepwalkers on the opening of the war before battle, who's also very good and more sympathetic to Austria-Hungary's situation.

But very good indeed.

Friday, December 22, 2017

Book Beginning: Terry Pratchett's Hogfather

Everything starts somewhere, although many physicists disagree.

...is the beginning of Terry Pratchett's Hogfather.

I'm not sure I think that's an especially engaging opening--it's the whole opening paragraph, not just the opening sentence--but I'm not sure I think openings are Terry Pratchett's strength. The Hogfather is the Santa Claus-like figure of Terry Pratchett's Discworld universe, though that's Death taking his place on Hogswatch Eve on the cover of my edition. It seems the Assassin's Guild has something to do with that.

Book Beginnings on Fridays is a bookish meme hosted by Gilion at Rose City Reader. To play, quote the beginning of the book you're currently reading, give the author and title, and any thoughts if you like. Happy Hogswatch to all!

Tuesday, December 19, 2017

Back To The Classics 2018 Signup

The idea is to read twelve classics over the next year corresponding to categories listed below. It's hosted by Karen at Books and Chocolate (what a lovely combination!) and it sounds like fun, so I'm trying it this year.

I'm sure I'll futz with the selections I've made--probably all year long--but here are the categories and the tentative choices I've matched against them:

A 19th Century Classic: Silas Marner by George Eliot

A 20th Century Classic:

Well, I was going to (still intend to?...) read The Death Of Virgil, but got distracted by:

Yevgeny Zamyatin's We

A Woman Author: Adam Bede by George Eliot

A Classic in Translation: Jean-Christophe by Romain Rolland

--I've been reading some other WWI stuff lately

A Children's Classic: Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

A Crime Classic: Trent's Last Case by E. C. Bentley

A Travel Classic: A Tramp Abroad by Mark Twain

A Single Word Title: Romola by George Eliot

--Hmmm....I seem to have a yen to read George Eliot this year

A Classic With A Color In The Title: Black Arrow by R. L. Stevenson

A Classic By An Author New To Me: The Leopard by Giuseppe Tommasi di Lampedusa

A Classic That Scares Me: Dracula by Bram Stoker

--A lot of people pick long books for this one; but I'm easily scared by scary things. Hence Dracula!

Reread A Favorite Classic:

Well, both of those still sound good, but I got to this one first:

Charles Dickens' The Mystery of Edwin Drood

Friday, December 15, 2017

Book Beginning: Barbara Tuchman's The Guns of August

So gorgeous was the spectacle on the May morning of 1910 when nine kings rode in the funeral of Edward VII of England that the crowd, waiting in hushed and black-clad awe, could not keep back gasps of admiration. In scarlet and blue and green and purple, three by three the sovereigns rode through the palace gates, with plumed helmets, gold braid, crimson sashes, and jeweled orders flashing in the sun.

...is the beginning of Barbara Tuchman's The Guns of August, her history of the opening of the first World War.

I was pretty taken with that opening, the grand spectacle, the last moment of concord before the coming storm of her subject. Perhaps the writing is a little overwrought, but it did involve nine living kings and one dead.

Book Beginnings on Fridays is a bookish meme hosted by Gilion at Rose City Reader. To play, quote the beginning of the book you're currently reading, give the author and title, and any thoughts if you like. Week #3!

Thursday, December 14, 2017

Ngaio Marsh's Tied Up In Tinsel

I was looking at a list of Christmas-themed books and realized I already owned this and hadn't read it. Good enough! It moved to the top of my chair-side pile.

Tied Up In Tinsel (1971) is a late Inspector Roderick Alleyn mystery by Ngaio Marsh. Alleyn himself is rather late in arriving in this one--he's wrapping up a case in the Antipodes--and is represented by his wife Troy, who is doing a portrait of Hilary Bill-Tasman, the owner of the country house where events take place.

The story starts in the days leading up to Christmas as guests arrive and it will culminate with a rather pagan festival in which Bill-Tasman's uncle Fred, dressed as a druid, pulls a sleigh loaded with gifts off the lawn and in through the French doors for the waiting children of the neighborhood.

It's a country house murder. Just in case you were worried about outsiders sneaking in, the house is surrounded by new-fallen snow that evening.

The most amusing thing about this is in the early setup. Bill-Tasman has just bought and restored the old family estate; he needs servants for it; but servants are expensive and hard-to-find. So Bill-Tasman hires released murderers, not habitual murderers, but 'oncers', because he can claim to be rehabilitating them and because they're cheap. Do you smell red herring, whatever that might smell like? Me, too.

Uncle Fred's valet goes missing after the Christmas performance. A bloodied poker is discovered, and then eventually the body.

Of course, Marsh adheres to the rules (Van Dine's #11) and it is not a servant who committed the crime, however murderous they may have been in the past. Which, I'm afraid, was the main problem with this. Quite a lot of the business in this was taken up with making the servants look possibly guilty. The formerly murderous servants are certainly convinced everyone will assume one of them is guilty. And the local constabulary as well as the guests do assume one of them is guilty. But Roderick Alleyn does not, and we don't either. So the middle of the novel is hard to take seriously and then the wrap up--there aren't that many guests in the house--is too swift. But Marsh is an old pro, she'd been writing these for almost forty years at this point, and the show must go on and does. (Theatrical double entendre definitely intended.) It's a success, though perhaps not her strongest.

That's Alf Moult, Uncle Fred's valet, on the cover, looking blue and frozen and quite dead in the snow in a story-appropriate, but not very appealing, cover photo for my Fontana edition.

Silver Age. Snow/Snowy Scene. My Reader's Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt.

Tied Up In Tinsel (1971) is a late Inspector Roderick Alleyn mystery by Ngaio Marsh. Alleyn himself is rather late in arriving in this one--he's wrapping up a case in the Antipodes--and is represented by his wife Troy, who is doing a portrait of Hilary Bill-Tasman, the owner of the country house where events take place.

The story starts in the days leading up to Christmas as guests arrive and it will culminate with a rather pagan festival in which Bill-Tasman's uncle Fred, dressed as a druid, pulls a sleigh loaded with gifts off the lawn and in through the French doors for the waiting children of the neighborhood.

It's a country house murder. Just in case you were worried about outsiders sneaking in, the house is surrounded by new-fallen snow that evening.

The most amusing thing about this is in the early setup. Bill-Tasman has just bought and restored the old family estate; he needs servants for it; but servants are expensive and hard-to-find. So Bill-Tasman hires released murderers, not habitual murderers, but 'oncers', because he can claim to be rehabilitating them and because they're cheap. Do you smell red herring, whatever that might smell like? Me, too.

Uncle Fred's valet goes missing after the Christmas performance. A bloodied poker is discovered, and then eventually the body.

Of course, Marsh adheres to the rules (Van Dine's #11) and it is not a servant who committed the crime, however murderous they may have been in the past. Which, I'm afraid, was the main problem with this. Quite a lot of the business in this was taken up with making the servants look possibly guilty. The formerly murderous servants are certainly convinced everyone will assume one of them is guilty. And the local constabulary as well as the guests do assume one of them is guilty. But Roderick Alleyn does not, and we don't either. So the middle of the novel is hard to take seriously and then the wrap up--there aren't that many guests in the house--is too swift. But Marsh is an old pro, she'd been writing these for almost forty years at this point, and the show must go on and does. (Theatrical double entendre definitely intended.) It's a success, though perhaps not her strongest.

That's Alf Moult, Uncle Fred's valet, on the cover, looking blue and frozen and quite dead in the snow in a story-appropriate, but not very appealing, cover photo for my Fontana edition.

Silver Age. Snow/Snowy Scene. My Reader's Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt.

Tuesday, December 12, 2017

European Reading Challenge 2018 Signup

This is a challenge to read and review books as a tour of Europe. It is hosted by Gilion at RoseCityReader. One author, one country, one book with fifty countries to choose from. I'm going to shoot for at least five (Deluxe Entourage). Here's the list of countries to choose from:

1.) The Odyssey (tr. by Emily Wilson.) Greece

2.) Arthur Schnitzler's Casanova's Return To Venice. Austria

3.) Jorge Carrión's Bookshops: A Reader's History. Spain

4.) Italo Calvino's The Baron In The Trees. Italy

5.) Amélie Nothomb's Pétronille. Belgium

6.) George Eliot's Silas Marner. UK

7.) Duc de la Rochefoucauld's Maxims. France

8.) Olga Tokarczuk's Flights. Poland

9.) Yevgeny Zamyatin's We. Russia

10.) Herta Müller's The Land Of Green Plums. Romania

11.) Ismail Kadare's Broken April. Albania

12.) Dubravka Ugresic' Fox. Croatia

13.) Romain Rolland's Jean-Christophe. Switzerland

14.) Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca. Monaco

15.) Jenny Erpenbeck's Go, Went, Gone. Germany

16.) Antonio Tabucchi's Time Ages In A Hurry. Hungary

Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Macedonia, Romania, Russia, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and Vatican City.The number of countries I can cover without rereading or acquiring new books (i.e., already on my TBR list) is more than I really care to think about, though, in fact, I have been thinking about just that.

1.) The Odyssey (tr. by Emily Wilson.) Greece

2.) Arthur Schnitzler's Casanova's Return To Venice. Austria

3.) Jorge Carrión's Bookshops: A Reader's History. Spain

4.) Italo Calvino's The Baron In The Trees. Italy

5.) Amélie Nothomb's Pétronille. Belgium

6.) George Eliot's Silas Marner. UK

7.) Duc de la Rochefoucauld's Maxims. France

8.) Olga Tokarczuk's Flights. Poland

9.) Yevgeny Zamyatin's We. Russia

10.) Herta Müller's The Land Of Green Plums. Romania

11.) Ismail Kadare's Broken April. Albania

12.) Dubravka Ugresic' Fox. Croatia

13.) Romain Rolland's Jean-Christophe. Switzerland

14.) Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca. Monaco

15.) Jenny Erpenbeck's Go, Went, Gone. Germany

16.) Antonio Tabucchi's Time Ages In A Hurry. Hungary

Sunday, December 10, 2017

Robert Heinlein's Time For The Stars

Robert Heinlein's Time For The Stars is one of his so-called juveniles, a genre we might now call middle grade or possibly young adult. This one dates from 1956. It's the first of his juveniles I've read.

Humans have explored and colonized Sol's existing planets and now it's time to think about exploring the rest of space. But the distances are long. How do ships stay in contact with each other or with Earth? How do they report what they find? The Long Range Foundation suspects that when identical twins say they each know what the other is thinking, it's more than metaphor. It turns out that, yes, ten percent of identical twins are actually telepathic and communicate instantaneously. Tom and Pat are one such pair of twins.

Tom tells his story as half of a communication team. After some complications, it's Tom who sets out with the spaceship, the Lewis and Clark, or, as she's familiarly known, the Elsie, and Pat who is left on Earth to receive reports and forward on news and new directives. The ship lands on a couple of candidate planets, one of which features the dinosaur-looking animal on the cover.

But in fact the encounters with alien lifeforms are not the real point of interest in the novel. Rather it's the tensions on board a ship that is isolated to its crew of two hundred, and the relationship between the travellers and those back home.

Two things struck me about this. Having just read an Ellery Queen mystery where psychology was an important motif, it was interesting to see it here, too. Of course, a psychologist would be important to make sure a crew of two hundred confined to one ship all got along, but the psychologist in this was treated as more all-wise and benevolent than I suspect any psychologist would get treated today. A skepticism about psychotherapy has appeared that just wasn't there in 1956.

The other thing that struck me about this is the melancholy tone. Tom, traveling at near the speed of light, ages much more slowly than do all of his friends and family back on Earth. The people around him die; it's a dangerous mission. Of course, melancholy and book-reading teenage boys--the presumed audience for this--are not exactly unrelated, but I was a little surprised to see it indulged. I thought they were supposed to like their adventure more pure...

Heinlein's politics are what they are, of course. It was a little odd to hear a sixteen year old boy grousing about those gummint bureaucrats, and suddenly I was aware of Heinlein as narrator rather than Tom, but mostly it was a story told well.

Enjoyable!

Humans have explored and colonized Sol's existing planets and now it's time to think about exploring the rest of space. But the distances are long. How do ships stay in contact with each other or with Earth? How do they report what they find? The Long Range Foundation suspects that when identical twins say they each know what the other is thinking, it's more than metaphor. It turns out that, yes, ten percent of identical twins are actually telepathic and communicate instantaneously. Tom and Pat are one such pair of twins.

Tom tells his story as half of a communication team. After some complications, it's Tom who sets out with the spaceship, the Lewis and Clark, or, as she's familiarly known, the Elsie, and Pat who is left on Earth to receive reports and forward on news and new directives. The ship lands on a couple of candidate planets, one of which features the dinosaur-looking animal on the cover.

But in fact the encounters with alien lifeforms are not the real point of interest in the novel. Rather it's the tensions on board a ship that is isolated to its crew of two hundred, and the relationship between the travellers and those back home.

Two things struck me about this. Having just read an Ellery Queen mystery where psychology was an important motif, it was interesting to see it here, too. Of course, a psychologist would be important to make sure a crew of two hundred confined to one ship all got along, but the psychologist in this was treated as more all-wise and benevolent than I suspect any psychologist would get treated today. A skepticism about psychotherapy has appeared that just wasn't there in 1956.

The other thing that struck me about this is the melancholy tone. Tom, traveling at near the speed of light, ages much more slowly than do all of his friends and family back on Earth. The people around him die; it's a dangerous mission. Of course, melancholy and book-reading teenage boys--the presumed audience for this--are not exactly unrelated, but I was a little surprised to see it indulged. I thought they were supposed to like their adventure more pure...

Heinlein's politics are what they are, of course. It was a little odd to hear a sixteen year old boy grousing about those gummint bureaucrats, and suddenly I was aware of Heinlein as narrator rather than Tom, but mostly it was a story told well.

Enjoyable!

Friday, December 8, 2017

Book Beginning: Robert Heinlein's Time For The Stars

According to their biographies, Destiny's favored children usually had their lives planned out from scratch. Napoleon was figuring out how to rule France when he was a barefoot boy in Corsica, Alexander the Great much the same, and Einstein was muttering equations in his cradle.

Maybe so. Me, I just muddled along....is the beginning to Robert Heinlein's Time For The Stars of 1956.

I have to say I was pretty amused by the sly way in which the narrator compares himself to Napoleon, Alexander, and Einstein. Two conquerors and a scientist. It's a boy's adventure, but for a boy good at math. We'll see if it can maintain that high level.

Book Beginnings on Fridays is a bookish meme hosted by Gilion at Rose City Reader. To play, quote the beginning of the book you're currently reading, give the author and title, and any thoughts if you like.

Thursday, December 7, 2017

Monthly Motif 2018 Signup

I saw this at MyReadersBlock and I thought this challenge from girlxoxo looked like a fun way to add some other categories to my reading list, so here I go with another challenge.

The challenge is to read one book for each of the twelve monthly categories listed below.

I'll pick as I go along because if I tried to decide now I'd change my mind for sure. But Alan Hollinghurst and James Baldwin are floating high in my TBR pile at the moment, so January will likely be one of those two. (James Baldwin would double count in the category!)

JANUARY – Diversify Your Reading

Kick the reading year off right and shake things up. Read a book with a character (or written by an author) of a race, religion, or sexual orientation other than your own.

N. K. Jemisin's The Fifth Season

Kick the reading year off right and shake things up. Read a book with a character (or written by an author) of a race, religion, or sexual orientation other than your own.

N. K. Jemisin's The Fifth Season

FEBRUARY – One Word

Read a book with a one word title.

I'm in the middle of three books with one word titles as I write this, but the shortest one got finished first...

Amélie Nothomb's Pétronille

Read a book with a one word title.

I'm in the middle of three books with one word titles as I write this, but the shortest one got finished first...

Amélie Nothomb's Pétronille

MARCH – Travel the World

Read a book set in a different country than your own, written by an author from another country than your own, or a book in which the characters travel.

Ben Lerner's Leaving The Atocha Station (Spain)

Read a book set in a different country than your own, written by an author from another country than your own, or a book in which the characters travel.

Ben Lerner's Leaving The Atocha Station (Spain)

APRIL – Read Locally

Read a book set in your country, state, town, village (or has a main character from your home town, country, etc)

Matt Cohen's The Bookseller

Read a book set in your country, state, town, village (or has a main character from your home town, country, etc)

Matt Cohen's The Bookseller

MAY- Book to Screen

Read a book that’s been made into a movie or a TV show.

Giuseppe di Lampedusa's The Leopard

We got this from the local video store a couple of years ago when the Other Reader (cf. Italo Calvino's If On A Winter's Night A Traveler) read it. The DVD was flawed and we got our money back, but from what we could see, it was a great movie. They're doing an Italian retrospective at TIFF Lightbox here in Toronto over the summer, and I'm planning on seeing it properly on the big screen when it appears later this summer. Burt Lancaster as the Prince, and Claudia Cardinale, too!

Read a book that’s been made into a movie or a TV show.

Giuseppe di Lampedusa's The Leopard

We got this from the local video store a couple of years ago when the Other Reader (cf. Italo Calvino's If On A Winter's Night A Traveler) read it. The DVD was flawed and we got our money back, but from what we could see, it was a great movie. They're doing an Italian retrospective at TIFF Lightbox here in Toronto over the summer, and I'm planning on seeing it properly on the big screen when it appears later this summer. Burt Lancaster as the Prince, and Claudia Cardinale, too!

JUNE- Crack the Case

Mysteries, True Crime, Who Dunnit’s.

E. C. Bentley's Trent's Last Case

Should be an easy category for me; this is the first mystery I read this month.

Mysteries, True Crime, Who Dunnit’s.

E. C. Bentley's Trent's Last Case

Should be an easy category for me; this is the first mystery I read this month.

JULY – Vacation Reads

Read a book you think is a perfect vacation read and tell us why.

Mary McCarthy's The Group

Because I get to read undistracted at the cabin!

Read a book you think is a perfect vacation read and tell us why.

Mary McCarthy's The Group

Because I get to read undistracted at the cabin!

AUGUST- Award Winners

Read a book that has won a literary award or a book written by an author who has been recognized in the bookish community.

Muriel Barbery's The Elegance Of The Hedgehog

It won several French prizes on its way to becoming a bestseller.

Read a book that has won a literary award or a book written by an author who has been recognized in the bookish community.

Muriel Barbery's The Elegance Of The Hedgehog

It won several French prizes on its way to becoming a bestseller.

SEPTEMBER- Don’t Turn Out The Light

Cozy mystery ghost stories, paranormal creeptastic, horror novels.

What better than....

Bram Stoker's Dracula

Cozy mystery ghost stories, paranormal creeptastic, horror novels.

What better than....

Bram Stoker's Dracula

OCTOBER- New or Old

Choose a new release from 2018 or a book known as a classic.

How 'bout a Nobel Prize winner?

Romain Rolland's Jean-Christophe

Choose a new release from 2018 or a book known as a classic.

How 'bout a Nobel Prize winner?

Romain Rolland's Jean-Christophe

NOVEMBER- Family

Books where family dynamics play a big role in the story

Let's restructure the family according to our new dystopian principles!

Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale

Books where family dynamics play a big role in the story

Let's restructure the family according to our new dystopian principles!

Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale

DECEMBER- Wrapping It Up

Winter or holiday themed books or books with snow, ice, etc in the title or books set in winter OR read a book with a theme from any of the months in this challenge (could be a theme you didn’t do, or one you want to do again).

Nicholas Blake's The Corpse In The Snowman

Winter or holiday themed books or books with snow, ice, etc in the title or books set in winter OR read a book with a theme from any of the months in this challenge (could be a theme you didn’t do, or one you want to do again).

Nicholas Blake's The Corpse In The Snowman

Monday, December 4, 2017

Ellery Queen's Ten Days' Wonder

Ten Days' Wonder is an Ellery Queen mystery from 1948. Though it starts briefly in New York City, it quickly becomes a Wrightsville mystery, that small New England town where Ellery has to do without his homicide detective father, and all of his father's apparatus.

Howard van Horn is suffering from something at the beginning of the novel and is subject to amnesiac spells. What is that something isn't quite clear, but it's clear he is suffering. After the latest spell he ends up in a Bowery flophouse; on coming back out of it, he hunts up Ellery to ask his help. Ellery agrees to go to Wrightsville.

It's clear to Ellery from the very beginning that Howard is hiding something.

In the immediate postwar period, the cousins Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee became interested in psychotherapy; it was in the air; psychotherapeutic analysis in general takes off in the U.S. at the time. The first DSM manual of mental health is issued in 1952, for example. There are several Ellery Queen novels in which psychotherapeutic explanations are important; in the next Ellery Queen mystery, The Cat of Many Tails, one of the main characters in the mystery, Dr. Cazalis, is a psychologist.

And in this mystery psychological explanations feature as well. Ellery is quite sure that there is a psychological explanation for Howard's amnesia that could be solved by a good analyst. Ellery is both right and wrong about this.

In fact Ellery turns out to be quite wrong in this one for a long while. Dannay and Lee use Ellery himself to supply wrong theories as a red herring not infrequently. It's sometimes said this is a feature of middle period Ellery Queen, and it is, but it goes back at least to The Greek Coffin Mystery. The consequences of Ellery's errors, though, are greater in the mysteries of this period, and especially in this one. Indeed, Ellery says at the end to the murderer, the actual murderer, "You've damaged my belief in myself. How can I ever play little tin god? I can't. I wouldn't dare.... You've made it impossible for me to go on. I'm finished. I can never take another case."

Though, of course, he does. This scene occurs early in that next novel, The Cat of Many Tails:

Anyway, Ten Days' Wonder is very satisfying. I did find the psychology a little heavy-handed here; it's handled with more subtlety in other Queen novels. There's an ill-conceived project that Ellery goes along with for a while; the last step in that project, it's hard to see how or why he would. Still the final reversal was very good and very well setup. Recommended.

And surprisingly the cover was actually designed by someone who had read the novel. Oh, dear, I want to say why that cover's so good, but anything I can think of to say, feels like it might be a bit spoiler-y. In any case, that is a:

Hangman's Noose, Golden Age. My Readers' Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt.

I have the feeling I've read this one before, but the computer says I haven't, and since the computer never lies, it's also...a Mount TBR book.

Howard van Horn is suffering from something at the beginning of the novel and is subject to amnesiac spells. What is that something isn't quite clear, but it's clear he is suffering. After the latest spell he ends up in a Bowery flophouse; on coming back out of it, he hunts up Ellery to ask his help. Ellery agrees to go to Wrightsville.

It's clear to Ellery from the very beginning that Howard is hiding something.

In the immediate postwar period, the cousins Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee became interested in psychotherapy; it was in the air; psychotherapeutic analysis in general takes off in the U.S. at the time. The first DSM manual of mental health is issued in 1952, for example. There are several Ellery Queen novels in which psychotherapeutic explanations are important; in the next Ellery Queen mystery, The Cat of Many Tails, one of the main characters in the mystery, Dr. Cazalis, is a psychologist.

And in this mystery psychological explanations feature as well. Ellery is quite sure that there is a psychological explanation for Howard's amnesia that could be solved by a good analyst. Ellery is both right and wrong about this.

In fact Ellery turns out to be quite wrong in this one for a long while. Dannay and Lee use Ellery himself to supply wrong theories as a red herring not infrequently. It's sometimes said this is a feature of middle period Ellery Queen, and it is, but it goes back at least to The Greek Coffin Mystery. The consequences of Ellery's errors, though, are greater in the mysteries of this period, and especially in this one. Indeed, Ellery says at the end to the murderer, the actual murderer, "You've damaged my belief in myself. How can I ever play little tin god? I can't. I wouldn't dare.... You've made it impossible for me to go on. I'm finished. I can never take another case."

Though, of course, he does. This scene occurs early in that next novel, The Cat of Many Tails:

"I don't want to hear about a case," Ellery would say. "Just let me be."But then his father gets assigned the case of the Cat, and Ellery is lured in.

"What's the matter?" his father would jeer. "Afraid you might be tempted?"

"I've given all that up."

Anyway, Ten Days' Wonder is very satisfying. I did find the psychology a little heavy-handed here; it's handled with more subtlety in other Queen novels. There's an ill-conceived project that Ellery goes along with for a while; the last step in that project, it's hard to see how or why he would. Still the final reversal was very good and very well setup. Recommended.

And surprisingly the cover was actually designed by someone who had read the novel. Oh, dear, I want to say why that cover's so good, but anything I can think of to say, feels like it might be a bit spoiler-y. In any case, that is a:

Hangman's Noose, Golden Age. My Readers' Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt.

I have the feeling I've read this one before, but the computer says I haven't, and since the computer never lies, it's also...a Mount TBR book.

Friday, December 1, 2017

Book Beginning: Ellery Queen's Ten Days' Wonder

"In the beginning it was without form, a darkness that kept shifting like dancers."

...is the beginning of Ellery Queen's mystery of 1948, Ten Days' Wonder.

It sounds like it ought to be the beginning of some religious or philosophical text, but in fact it's the beginning of a description of a massive hangover on the part of the main character Howard van Horn. Or is it? Things that look like religion but aren't quite upon investigation is a trick Ellery Queen uses more than once.

Book Beginnings on Fridays is a bookish meme hosted by Gilion at Rose City Reader. To play, quote the beginning of the book you're currently reading, give the author and title, and any thoughts if you like. This is my first time in, and it seems like a fun thing to do.

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

Erle Stanley Gardner's The Case Of The Lonely Heiress

"There are times when a lawyer throws the rule book away, when he has to go by hunches." Oh, really? You don't say, Mr. Mason? Are there actually any other times in your law practice, Mr. Mason? In any case, this isn't one of those other times. But you wouldn't want to read about those other times anyway.

The copyright in my reprint of Erle Stanley Gardner's The Case Of The Lonely Heiress says it first came out in February of 1948. Maybe it was Gardner's first novel of that year. I doubt it was his last.

The setup is pretty good in this one. Robert Caddo is the publisher of a somewhat sleazy lonely hearts magazine. Women post ads in his magazine. The back of the magazine has a mailing coupon to contact these lonely women c/o Robert Caddo's magazine office, which he then forwards on to an anonymous box for the woman posting a particular ad. That's all fine and mildly lucrative. Then a woman posts an ad saying she's a young, good-looking heiress (not someone middle-aged whose parent has just died) and it's a hit. Caddo's magazine is flying off the shelves. But it's a little too much of a hit for the local vice squad who thinks Caddo has just gotten that much closer to pimping.

Caddo goes to Mason to prove that this advertisement is legit since he's created a structure whereby he doesn't actually know the women involved. Perry, with Paul Drake's help, identifies the lonely heiress of the title advertising in Caddo's magazine. She really is looking for a man, though for what purpose isn't quite clear at the start.

Caddo is a bit of a sleaze bucket. This is before internet dating, though the process is kind of analogous, and it was inevitable I suppose that he had to be. Della says:

After the setup, though, it deteriorates a bit. As you knew (unless you've never read a Perry Mason novel and you've never seen the television show) the lonely heiress, blonde and fur-coated on the cover of my copy, will go to Perry, engage him as her lawyer, and then promptly be suspected of murder. That's the convention, and conventions are useful. The real question is, who is the person who really did it, and how will Perry make a fool of Hamilton Burger?

Well. Hamilton Burger doesn't even show up in this one. The D.A. is James Hanover and he's not particularly confounded or interesting. The revelation of the actual murderer isn't especially surprising. And, while this is a short novel, it even feels a little padded. Remember how your fifth grade teacher taught you in writing an essay to first say what you were going to say, then say it, then remind your reader what it was you said? Yeah, me too. That may be good advice for making your essay clear and comprehensible, and it may also be good advice for padding out your word count. It's less good advice if you're writing a novel, but it's advice Gardner had in his head, I'm afraid. He may have needed the word count. Perry and Della decide what they're going to do when they break into a witness's apartment, then they do almost exactly that, and then the information shows up in the courtroom. Okay, we get it.

On the subject of rom com subplots, though, this one was a winner. I don't think of this as a usual item in my Perry Mason universe: there's merely the eternal question of when will Perry realize that Della is unspokenly pining for him. Here he takes her out for Chinese and dancing as a variant instead of a steak. But this one has another, more realized flirtation. The lonely heiress ends up with one of Paul Drake's detectives. Romance!

Summation: not the best, but if you like Perry Mason and are looking for a bit of fluff, you'll like this.

Golden Age. Blonde (and in a fur coat!) My Reader's Block Vintage Mystery Cover Scavenger Hunt.

The copyright in my reprint of Erle Stanley Gardner's The Case Of The Lonely Heiress says it first came out in February of 1948. Maybe it was Gardner's first novel of that year. I doubt it was his last.

The setup is pretty good in this one. Robert Caddo is the publisher of a somewhat sleazy lonely hearts magazine. Women post ads in his magazine. The back of the magazine has a mailing coupon to contact these lonely women c/o Robert Caddo's magazine office, which he then forwards on to an anonymous box for the woman posting a particular ad. That's all fine and mildly lucrative. Then a woman posts an ad saying she's a young, good-looking heiress (not someone middle-aged whose parent has just died) and it's a hit. Caddo's magazine is flying off the shelves. But it's a little too much of a hit for the local vice squad who thinks Caddo has just gotten that much closer to pimping.

Caddo goes to Mason to prove that this advertisement is legit since he's created a structure whereby he doesn't actually know the women involved. Perry, with Paul Drake's help, identifies the lonely heiress of the title advertising in Caddo's magazine. She really is looking for a man, though for what purpose isn't quite clear at the start.

Caddo is a bit of a sleaze bucket. This is before internet dating, though the process is kind of analogous, and it was inevitable I suppose that he had to be. Della says:

You can take a look at Bob Caddo and see what he is. One of those old wolves that run around pawing girls and trying to cut corners.Timely!

After the setup, though, it deteriorates a bit. As you knew (unless you've never read a Perry Mason novel and you've never seen the television show) the lonely heiress, blonde and fur-coated on the cover of my copy, will go to Perry, engage him as her lawyer, and then promptly be suspected of murder. That's the convention, and conventions are useful. The real question is, who is the person who really did it, and how will Perry make a fool of Hamilton Burger?

Well. Hamilton Burger doesn't even show up in this one. The D.A. is James Hanover and he's not particularly confounded or interesting. The revelation of the actual murderer isn't especially surprising. And, while this is a short novel, it even feels a little padded. Remember how your fifth grade teacher taught you in writing an essay to first say what you were going to say, then say it, then remind your reader what it was you said? Yeah, me too. That may be good advice for making your essay clear and comprehensible, and it may also be good advice for padding out your word count. It's less good advice if you're writing a novel, but it's advice Gardner had in his head, I'm afraid. He may have needed the word count. Perry and Della decide what they're going to do when they break into a witness's apartment, then they do almost exactly that, and then the information shows up in the courtroom. Okay, we get it.

On the subject of rom com subplots, though, this one was a winner. I don't think of this as a usual item in my Perry Mason universe: there's merely the eternal question of when will Perry realize that Della is unspokenly pining for him. Here he takes her out for Chinese and dancing as a variant instead of a steak. But this one has another, more realized flirtation. The lonely heiress ends up with one of Paul Drake's detectives. Romance!

Summation: not the best, but if you like Perry Mason and are looking for a bit of fluff, you'll like this.

Golden Age. Blonde (and in a fur coat!) My Reader's Block Vintage Mystery Cover Scavenger Hunt.

Saturday, November 25, 2017

John Dickson Carr's To Wake The Dead

To Wake The Dead is a Dr. Gideon Fell mystery by John Dickson Carr from 1938. It has an odd, and frankly pretty unnecessary, setup in which Christopher Kent discovers the body of his cousin-in-law Jenny Kent in the top floor of a luxury hotel. He's been incommunicado for six weeks so he doesn't know that his cousin Rodney, Jenny's husband, has also been murdered in the same brutal fashion: strangled and then beaten around the face.

While I wouldn't exactly call this a cozy, it is Golden Age, and the brutality isn't dwelt on. Thankfully.

The top floor where Jenny Kent was murdered is entirely taken up by a party associated with South African millionaire Dan Reaper. For various reasons no one else has access to the top floor, or so it seems, establishing a country house murder scenario, without the country house.

Rodney Kent's earlier murder occurs in an actual country house with the same limited set of suspects.

As a fair-play cluing mystery, this was a superb entry. Everything was there to point to the murderer, but for me at least the killer came as a complete surprise. Perhaps the killer's seeming alibi for Jenny Kent's murder was a little improbable, but there were enough hints that it didn't seem unfair. And as I say I had no idea who it would be. Quite often in a Golden Age mystery I know who will turn out the killer less by the clues than by how the author writes about the killer.

There was a romantic comedy side plot in this one, but it felt like a bit of an afterthought. It involved Christopher Kent and one of the suspects. Now--of course--the mystery should be the main thing in a mystery novel, but I like a romantic comedy side plot, and Carr can and did do better. Oh, well.

I also thought about structure in this in a way I'm not really sure I should. But it brings up an interesting point.

In the beginning, there was Watson. (Well, not really, but go with me.) Our entry point into the story was not the genius detective, but the sidekick who was writing the story. Sidekicks can be first-person narrators or third-person focus characters. They can be useful and relatively competent (Watson of the books or Archie Goodwin) or amiable duffers (Nigel Bruce as Watson). Agatha Christie starts with Hastings as Poirot's regular sidekick before gradually letting him slip away.

The detective can be the focal point. This is certainly the case with the hard boiled style: the Continental Op, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe. But many of the Ellery Queen mysteries work this way, too, as do the Perry Mason novels. As a general rule, the focal point character is present in every scene. Scenes where that character wasn't present can only appear by report.

We can also have no single character through whose eyes we see events, but shift as needed. This is less used in mysteries, though standard in literary fiction, especially of an earlier era. Partly this is because then what do you do with the murderer's thoughts? In any case Msgr. Knox forbade that in his list of rules, though yes, it does happen.

And you can have a one-time sidekick. That's what Carr does in this one, and while I haven't by any means read all of Carr's novels, it seems a common approach for him and others. There are one-time sidekicks in Edmund Crispin's Gervase Fen mysteries as well, for example. In this mystery it's Christopher Kent who is present in every scene. But Christopher Kent is or should be a suspect! He's given an alibi very early to make it seem somewhat acceptable he's invited into the room when Dr. Fell or Inspector Hadley interview suspects. I've swallowed this device in other mysteries, but this time it stuck out as unduly improbable. I understand why you might not want a regularly occurring dunce, but if your detective is professional or semi-professional, (Dr. Gideon Fell, though he doesn't seem to be paid, is regularly consulted) it just seems improbable that an amateur implicated in the case gets to be in the room all the time.

Ah, well. An observation. But still enjoyable anyway.

Tombstone. Golden Age. My Readers Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt.

While I wouldn't exactly call this a cozy, it is Golden Age, and the brutality isn't dwelt on. Thankfully.

The top floor where Jenny Kent was murdered is entirely taken up by a party associated with South African millionaire Dan Reaper. For various reasons no one else has access to the top floor, or so it seems, establishing a country house murder scenario, without the country house.

Rodney Kent's earlier murder occurs in an actual country house with the same limited set of suspects.

As a fair-play cluing mystery, this was a superb entry. Everything was there to point to the murderer, but for me at least the killer came as a complete surprise. Perhaps the killer's seeming alibi for Jenny Kent's murder was a little improbable, but there were enough hints that it didn't seem unfair. And as I say I had no idea who it would be. Quite often in a Golden Age mystery I know who will turn out the killer less by the clues than by how the author writes about the killer.

There was a romantic comedy side plot in this one, but it felt like a bit of an afterthought. It involved Christopher Kent and one of the suspects. Now--of course--the mystery should be the main thing in a mystery novel, but I like a romantic comedy side plot, and Carr can and did do better. Oh, well.

I also thought about structure in this in a way I'm not really sure I should. But it brings up an interesting point.

In the beginning, there was Watson. (Well, not really, but go with me.) Our entry point into the story was not the genius detective, but the sidekick who was writing the story. Sidekicks can be first-person narrators or third-person focus characters. They can be useful and relatively competent (Watson of the books or Archie Goodwin) or amiable duffers (Nigel Bruce as Watson). Agatha Christie starts with Hastings as Poirot's regular sidekick before gradually letting him slip away.

The detective can be the focal point. This is certainly the case with the hard boiled style: the Continental Op, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe. But many of the Ellery Queen mysteries work this way, too, as do the Perry Mason novels. As a general rule, the focal point character is present in every scene. Scenes where that character wasn't present can only appear by report.

We can also have no single character through whose eyes we see events, but shift as needed. This is less used in mysteries, though standard in literary fiction, especially of an earlier era. Partly this is because then what do you do with the murderer's thoughts? In any case Msgr. Knox forbade that in his list of rules, though yes, it does happen.

And you can have a one-time sidekick. That's what Carr does in this one, and while I haven't by any means read all of Carr's novels, it seems a common approach for him and others. There are one-time sidekicks in Edmund Crispin's Gervase Fen mysteries as well, for example. In this mystery it's Christopher Kent who is present in every scene. But Christopher Kent is or should be a suspect! He's given an alibi very early to make it seem somewhat acceptable he's invited into the room when Dr. Fell or Inspector Hadley interview suspects. I've swallowed this device in other mysteries, but this time it stuck out as unduly improbable. I understand why you might not want a regularly occurring dunce, but if your detective is professional or semi-professional, (Dr. Gideon Fell, though he doesn't seem to be paid, is regularly consulted) it just seems improbable that an amateur implicated in the case gets to be in the room all the time.

Ah, well. An observation. But still enjoyable anyway.

Tombstone. Golden Age. My Readers Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt.

Wednesday, November 22, 2017

The Classics Club Challenge

I recently came across the Classics Club--I'm not even really sure where I saw it anymore--and I thought the idea of selecting a list of classics to read and discuss was exactly what I needed. There are a whole bunch of books that easily qualify for classic status around here that I haven't read and should. And want to, too! But a little motivation, like a publicly announced declaration to do so, never hurts.

So here's my list. I've selected fifty books* and limited myself to books that 1.) I already had, and 2.) I had not yet read (were on my TBR pile). I went through the suggested list of classics at the Classics Club website, those old Modern Library lists of fiction and non-fiction, problematic as they were, plus a few others that seemed pretty clearly classics. (Romain Rolland, Henryk Sienkewicz, Hermann Broch.) I also decided to aim for a mix of fiction and non-fiction, English and works in translation. Some short works, but also some really long ones, just to keep me honest. There were easily more than fifty available by my criteria, but I'll re-up as needed. It is now the 22nd of November, 2017, so that means by this same day in 2022, I'll have finished them all. Really!

English Language Fiction

1.) Margaret Atwood/The Handmaid's Tale

2.) James Baldwin/Giovanni's Room (read)

3.) James Baldwin/Go Tell It On The Mountain

4.) Samuel Butler/The Way Of All Flesh

5.) Willa Cather/A Lost Lady

6.) Willa Cather/One Of Ours

7.) Daphne du Maurier/Rebecca

8.) George Eliot/Adam Bede

9.) George Eliot/Romola

10.) George Eliot/Scenes of Clerical Life

11.) George Eliot/Silas Marner

12.) William Faulkner/Light In August

13.) John Galsworthy/The Forsyte Saga

14.) Oliver Goldsmith/The Vicar of Wakefield

15.) Thomas Hardy/Wessex Tales

16.) Henry James/The American

17.) Henry James/Wings of the Dove

18.) Malcolm Lowry/Under the Volcano

19.) W. Somerset Maugham/The Razor's Edge

20.) Toni Morrison/Song of Solomon

21.) Sylvia Plath/The Bell Jar

22.) J. F. Powers/Morte D'Urban

23.) Sir Walter Scott/Count Robert of Paris

24.) Robert Louis Stevenson/Black Arrow

25.) Bram Stoker/Dracula

26.) Edith Wharton/The Custom of the Country

27.) Edith Wharton/House of Mirth

28.) Virginia Woolf/The Waves

Fiction in Translation

29.) Anon/1001 Nights (Richard F. Burton translation)

30.) Honore de Balzac/Cousin Bette

31.) Giovanni Bocaccio/The Decameron

32.) Hermann Broch/The Death Of Virgil

33.) Johann Wolfgang von Goethe/Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship (read)

34.) Yasunari Kawabata/Snow Country

35.) Giuseppe di Lampedusa/The Leopard

36.) Romain Rolland/Jean-Christophe

37.) Henryk Sienkewicz/Quo Vadis

38.) Jules Verne/20000 Leagues Under The Sea

39.) Yevgeny Zamyatin/We

Non-Fiction

40.) James Baldwin/Notes of a Native Son

41.) Frederick Douglass/Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave

42.) Edmund Gibbon/The History of the Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire

43.) Plutarch/Lives (read)

44.) Bertrand Russell/A History of Western Philosophy

45.) Barbara Tuchman/The Guns of August

46.) Mark Twain/A Tramp Abroad

47.) Edmund Wilson/Axel's Castle

48.) Edmund Wilson/Patriotic Gore

49.) Mary Wollstonecraft/The Vindication of the Rights of Women

50.) Virginia Woolf/A Room Of One's Own

Plays

51.) George Bernard Shaw/Major Barbara (read)

52.) George Bernard Shaw/Pygmalion

53.) Richard Brinsley Sheridan/The School for Scandal

Poetry

54.) Thomas Hardy/Complete Poems

55.) Edmund Spenser/The Faerie Queene

*Whoops. I ended up with 55. I could trim it, but they're all such good books...

So here's my list. I've selected fifty books* and limited myself to books that 1.) I already had, and 2.) I had not yet read (were on my TBR pile). I went through the suggested list of classics at the Classics Club website, those old Modern Library lists of fiction and non-fiction, problematic as they were, plus a few others that seemed pretty clearly classics. (Romain Rolland, Henryk Sienkewicz, Hermann Broch.) I also decided to aim for a mix of fiction and non-fiction, English and works in translation. Some short works, but also some really long ones, just to keep me honest. There were easily more than fifty available by my criteria, but I'll re-up as needed. It is now the 22nd of November, 2017, so that means by this same day in 2022, I'll have finished them all. Really!

English Language Fiction

1.) Margaret Atwood/The Handmaid's Tale

2.) James Baldwin/Giovanni's Room (read)

3.) James Baldwin/Go Tell It On The Mountain

4.) Samuel Butler/The Way Of All Flesh

5.) Willa Cather/A Lost Lady

6.) Willa Cather/One Of Ours

7.) Daphne du Maurier/Rebecca

8.) George Eliot/Adam Bede

9.) George Eliot/Romola

10.) George Eliot/Scenes of Clerical Life

11.) George Eliot/Silas Marner

12.) William Faulkner/Light In August

13.) John Galsworthy/The Forsyte Saga

14.) Oliver Goldsmith/The Vicar of Wakefield

15.) Thomas Hardy/Wessex Tales

16.) Henry James/The American

17.) Henry James/Wings of the Dove

18.) Malcolm Lowry/Under the Volcano

19.) W. Somerset Maugham/The Razor's Edge

20.) Toni Morrison/Song of Solomon

21.) Sylvia Plath/The Bell Jar

22.) J. F. Powers/Morte D'Urban

23.) Sir Walter Scott/Count Robert of Paris

24.) Robert Louis Stevenson/Black Arrow

25.) Bram Stoker/Dracula

26.) Edith Wharton/The Custom of the Country

27.) Edith Wharton/House of Mirth

28.) Virginia Woolf/The Waves

Fiction in Translation

29.) Anon/1001 Nights (Richard F. Burton translation)

30.) Honore de Balzac/Cousin Bette

31.) Giovanni Bocaccio/The Decameron

32.) Hermann Broch/The Death Of Virgil

33.) Johann Wolfgang von Goethe/Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship (read)

34.) Yasunari Kawabata/Snow Country

35.) Giuseppe di Lampedusa/The Leopard

36.) Romain Rolland/Jean-Christophe

37.) Henryk Sienkewicz/Quo Vadis

38.) Jules Verne/20000 Leagues Under The Sea

39.) Yevgeny Zamyatin/We

Non-Fiction

40.) James Baldwin/Notes of a Native Son

41.) Frederick Douglass/Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave

42.) Edmund Gibbon/The History of the Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire

43.) Plutarch/Lives (read)

44.) Bertrand Russell/A History of Western Philosophy

45.) Barbara Tuchman/The Guns of August

46.) Mark Twain/A Tramp Abroad

47.) Edmund Wilson/Axel's Castle

48.) Edmund Wilson/Patriotic Gore

49.) Mary Wollstonecraft/The Vindication of the Rights of Women

50.) Virginia Woolf/A Room Of One's Own

51.) George Bernard Shaw/Major Barbara (read)

52.) George Bernard Shaw/Pygmalion

53.) Richard Brinsley Sheridan/The School for Scandal

Poetry

54.) Thomas Hardy/Complete Poems

55.) Edmund Spenser/The Faerie Queene

*Whoops. I ended up with 55. I could trim it, but they're all such good books...

Tuesday, November 21, 2017

E. M. Forster's Where Angels Fear To Tread

Where Angels Fear To Tread was E. M. Forster's first published novel. It came out in 1905. I found the twists of the plot consistently surprising, and I'm reluctant to give much away. But the initial setup is this: Lilia Herriton, with Miss [Caroline] Abbott as her companion, set off for a year's journey to Italy. Lilia, aged 33, is the daughter-in-law of the formidable Mrs. Herriton. She had one child, a daughter, by her husband, Mrs. Herriton's elder son, before that son died. Lilia, not especially bright or wilful, is browbeaten into living according to Herriton family proprieties, and it is when she thinks of making a second marriage with a local curate that she is shipped off to Italy in the company of a companion. Problem solved.

Well, even worse happens there.

A letter arrives that Lilia is engaged to a member of the Italian nobility. Unsurprisingly, Gino's connection to any actual nobility is extremely tenuous; rather he's the son of a provincial dentist, much younger than Lilia, and he has just completed his mandatory military service. Panic ensues in the Herriton household. Philip, the younger son, is dispatched to Italy to deal with the problem.

I found it a very funny novel, despite the fact that some tragic things happen. Also despite, though maybe also because, Mrs. Herriton and her daughter Harriet are so awful, so priggish in the manners, so self-righteous, and so clueless. Philip is occasionally, but only occasionally, better. As a reader, I wanted a very severe comeuppance for all of them; it's only partly granted, I'm afraid.

Two things struck me particularly about this. About halfway through--it's a short novel, 150 pages or so in my edition--I was finding everybody so objectionable, I was half-thinking about giving the novel up. But as I said, I was also finding it funny. Now I know that I'm not supposed to base my valuation of a novel on whether there are any likeable characters; I'm sure they taught me that in graduate school. But as an actual reader, I do. Books that have somebody that you like at least a little--a saint is not required--provide an entrance for the reader into the material; they are also, I think, more realistic: it's important to acknowledge that the world has at least the possibility of someone likeable or something good. A novel such as I remember Less Than Zero to be--it's been a while since I've read it--where everybody is a monster is both a bit tedious to read, but also, I think, ultimately false. Where Angels Fear To Tread flirted with that, but then there were the occasional, surprising, bits of good behaviour.

The other thing that interested me particularly was Forster's handling of an outsider. Nowadays, of course, the son of an Italian dentist would hardly qualify, but 1900 was a different time. Italians were seen as poor and grasping, barely civilized, even as they lived among the ruins of civilization. I recently read Dickens' The Mystery of Edwin Drood and one of the important points in that novel is English society's view of two orphaned Eurasians. Eurasians were seen as treacherous and exotic and simply not like us in the Dickens novel, just as the Italians are in this one. Forster's handling of Gino is quite deft: we're given all the cliches about Italians, but in the person of Mrs. Herriton, so we discount them. But then maybe some of them are true: maybe Gino was interested in Lilia only for or primarily for her money. Forster's famed irony and ambiguity come into play here: when Philip and Gino sit down to discuss what Gino's price is, it's clear Gino understands what the topic of the discussion is from the start. No wounded innocence here. But what does he really think? Well, because Forster only looks at Gino from the outside, we don't entirely know, and that's fine, and an interesting way to go about it.

Anyway, an impressive novel and a funny one, even if with considerable darkness.

Well, even worse happens there.

A letter arrives that Lilia is engaged to a member of the Italian nobility. Unsurprisingly, Gino's connection to any actual nobility is extremely tenuous; rather he's the son of a provincial dentist, much younger than Lilia, and he has just completed his mandatory military service. Panic ensues in the Herriton household. Philip, the younger son, is dispatched to Italy to deal with the problem.

I found it a very funny novel, despite the fact that some tragic things happen. Also despite, though maybe also because, Mrs. Herriton and her daughter Harriet are so awful, so priggish in the manners, so self-righteous, and so clueless. Philip is occasionally, but only occasionally, better. As a reader, I wanted a very severe comeuppance for all of them; it's only partly granted, I'm afraid.

Two things struck me particularly about this. About halfway through--it's a short novel, 150 pages or so in my edition--I was finding everybody so objectionable, I was half-thinking about giving the novel up. But as I said, I was also finding it funny. Now I know that I'm not supposed to base my valuation of a novel on whether there are any likeable characters; I'm sure they taught me that in graduate school. But as an actual reader, I do. Books that have somebody that you like at least a little--a saint is not required--provide an entrance for the reader into the material; they are also, I think, more realistic: it's important to acknowledge that the world has at least the possibility of someone likeable or something good. A novel such as I remember Less Than Zero to be--it's been a while since I've read it--where everybody is a monster is both a bit tedious to read, but also, I think, ultimately false. Where Angels Fear To Tread flirted with that, but then there were the occasional, surprising, bits of good behaviour.

The other thing that interested me particularly was Forster's handling of an outsider. Nowadays, of course, the son of an Italian dentist would hardly qualify, but 1900 was a different time. Italians were seen as poor and grasping, barely civilized, even as they lived among the ruins of civilization. I recently read Dickens' The Mystery of Edwin Drood and one of the important points in that novel is English society's view of two orphaned Eurasians. Eurasians were seen as treacherous and exotic and simply not like us in the Dickens novel, just as the Italians are in this one. Forster's handling of Gino is quite deft: we're given all the cliches about Italians, but in the person of Mrs. Herriton, so we discount them. But then maybe some of them are true: maybe Gino was interested in Lilia only for or primarily for her money. Forster's famed irony and ambiguity come into play here: when Philip and Gino sit down to discuss what Gino's price is, it's clear Gino understands what the topic of the discussion is from the start. No wounded innocence here. But what does he really think? Well, because Forster only looks at Gino from the outside, we don't entirely know, and that's fine, and an interesting way to go about it.

Anyway, an impressive novel and a funny one, even if with considerable darkness.

Sunday, November 5, 2017

Leslie Charteris' The Last Hero

The Last Hero is a novel length adventure of the Saint that came out in 1930. In the usual way, the Saint has troubles with both the law, in the form of the police and the British secret service, and the bad guys, but more trouble with the bad guys. The bad guys also have more trouble with him.

It is definitely a novel of the period between the wars, and is concerned with the horrors of the last war, and preventing a new one. There's a middleman who hopes to make money on armaments when the shooting starts--a similar theme to Graham Greene's A Gun For Sale of 1936. There's also a bomb-throwing anarchist which the Saint stops in the very first scene.

Professor Vargan invents an electronic doomsday weapon which the Saint discovers by accident. Vargan, who is British, but disaffected, is willing to sell his weapon to anybody, but offers it first to the Brits, who are happy to take it. But the Crown Prince of an unspecified country is also after it. And Dr. Rayt Marius, tall and ugly, is just hoping to start a war as a way to make money. The Saint has to punch and shoot his way through to keep the secret out of everybody's hands, and to keep the next war from starting.

There were more bodies and more deliberate violence on the part of the Saint and his allies in this one. Though the Saint proclaims he's a warrior of sorts, quite frequently when the bad guys die it's through some excess of their own devising. This time less so.

On the whole I found this one less good than some. It was a little long, and felt bloated. At one point, the Saint and one of his allies make a mistake that allows Rayt Marius to escape so he can be present for the finale. It's always a bit disappointing in one's thrillers when somebody has to do something stupid to set up the tension, and Charteris doesn't improve the situation by writing in the Saint's defence that he was especially angry. On the other hand the Saint estimates that Chief Inspector Teal, his nemesis and occasional ally with Scotland Yard, who is tracking him in this one, is a day and a half behind him. Teal does better than that, showing twenty-four hours earlier than the Saint expected him to, and saving the Saint's bacon in the process. That's a much better way to have one's hero be less than perfect.

Anyway, good, but not great.

That's the caricature of the Saint on the cover, about to drop a bomb on the street below. But it was actually the anarchist who was about to throw the bomb and the Saint stopped him. Oh, well, reading the book never seems to be required of cover designers. In any case it is:

Any Other Weapon. Golden Age. My Reader's Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt.

It is definitely a novel of the period between the wars, and is concerned with the horrors of the last war, and preventing a new one. There's a middleman who hopes to make money on armaments when the shooting starts--a similar theme to Graham Greene's A Gun For Sale of 1936. There's also a bomb-throwing anarchist which the Saint stops in the very first scene.

Professor Vargan invents an electronic doomsday weapon which the Saint discovers by accident. Vargan, who is British, but disaffected, is willing to sell his weapon to anybody, but offers it first to the Brits, who are happy to take it. But the Crown Prince of an unspecified country is also after it. And Dr. Rayt Marius, tall and ugly, is just hoping to start a war as a way to make money. The Saint has to punch and shoot his way through to keep the secret out of everybody's hands, and to keep the next war from starting.

There were more bodies and more deliberate violence on the part of the Saint and his allies in this one. Though the Saint proclaims he's a warrior of sorts, quite frequently when the bad guys die it's through some excess of their own devising. This time less so.

On the whole I found this one less good than some. It was a little long, and felt bloated. At one point, the Saint and one of his allies make a mistake that allows Rayt Marius to escape so he can be present for the finale. It's always a bit disappointing in one's thrillers when somebody has to do something stupid to set up the tension, and Charteris doesn't improve the situation by writing in the Saint's defence that he was especially angry. On the other hand the Saint estimates that Chief Inspector Teal, his nemesis and occasional ally with Scotland Yard, who is tracking him in this one, is a day and a half behind him. Teal does better than that, showing twenty-four hours earlier than the Saint expected him to, and saving the Saint's bacon in the process. That's a much better way to have one's hero be less than perfect.

Anyway, good, but not great.

That's the caricature of the Saint on the cover, about to drop a bomb on the street below. But it was actually the anarchist who was about to throw the bomb and the Saint stopped him. Oh, well, reading the book never seems to be required of cover designers. In any case it is:

Any Other Weapon. Golden Age. My Reader's Block Vintage Mystery Scavenger Hunt.

Vintage Mystery Challenge 2018 Signup

Bev at MyReadersBlock has changed her vintage mystery challenge to a new format this year, titled Just the Facts, Ma'am and it looks like a fun one.

I've been having a good time reading along for this year's Vintage Mystery challenge, and I'm definitely up for another year.

Since I typically read more Golden Age mysteries than Silver Age (or contemporary for that matter) I'm going to go for the Detective Sergeant level, 12 or 2 in each category in the Golden Age and the Constable level of 6 or 1 in each category for the Silver Age.

Here are the category cards. I'm already enjoying thinking about what mysteries I might slot in against each type.

I've been having a good time reading along for this year's Vintage Mystery challenge, and I'm definitely up for another year.

Since I typically read more Golden Age mysteries than Silver Age (or contemporary for that matter) I'm going to go for the Detective Sergeant level, 12 or 2 in each category in the Golden Age and the Constable level of 6 or 1 in each category for the Silver Age.

Here are the category cards. I'm already enjoying thinking about what mysteries I might slot in against each type.

Gold:

Who

1.) E. R. Punshon's Music Tells All. Crime-solving duo.

2.) Rex Stout's Not Quite Dead Enough. In the armed services.

What

1.) Michael Innes' The Secret Vanguard. Pseudonymous Author.

2.) Erle Stanley Gardner's The Case Of The Haunted Husband. Alliterative Title.

When

1.) Michael Innes' Lament For A Maker. During A Recognized Holiday.

2.) Nicholas Blake's The Corpse In The Snowman. During a Weather Event. (Snowstorm)

Where

1.) Patricia Wentworth's Eternity Ring. In A Small Village.

2.) Michael Innes' Operation Pax. In a hospital/nursing home.

How

1.) Erle Stanley Gardner's The Case of the Velvet Claws. Death by Shooting

2.) Georgette Heyer's Footsteps In The Dark. Death by Strangulation

Why

1.) E. C. Bentley's Trent's Last Case. 'Best of' List.

2.) Charles Dickens' The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Favorite Author.

Silver:

Who

1.) Michael Innes' The New Sonia Wayward. Armed Services.

What

1.) Julian Symons' The Blackheath Poisonings. Means of Murder In The Title.

When

1.) Ellis Peters' Black Is The Colour Of My True Love's Heart. Special Event.

Where

1.) Peter Robinson's The Hanging Valley. Set In A Small Village.

How

1.) Ross Macdonald's The Blue Hammer. At Least Two Deaths By Different Means.

2.) L. R. Wright's The Suspect. Death by Blunt Instrument.

Why

1.) Erle Stanley Gardner's The Case Of The Spurious Spinster. TBR List.

Mount TBR 2018 Signup

I'm on schedule for my 2017 TBR challenge: I'm currently at 32 out of the 36 pledged, so I'm doing OK on that front.