The six main writers of Wilson's Axel's Castle are W. B. Yeats, Paul Valéry, T. S. Eliot, Marcel Proust, James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. So, you know, a pretty serious bunch. For Wilson, these are the representative Symbolists and his book is a study of 'imaginative literature of 1870 to 1930'."[These writers] break down the walls of the present and wake us to the hope and exaltation of the untried, unsuspected possibilities of human thought and art."

"...the symbols of the Symbolist school [unlike the cross for Christianity or the Stars and Stripes for the USA] are usually chosen arbitrarily by the poet to stand for for special ideas of his own--they are a sort of disguise for these ideas."

The book is full of sharp and unexpected insights on his subjects; on Proust, for instance:

"These latter scenes, indeed, contain so much broad humor and so much extravagant satire that, appearing in a modern French novel, they amaze us....it seems plain that Proust must have read Dickens and that this sometimes grotesque heightening of character had been partly learned from him."

Not what one thinks of when mentioning Proust, and yet it's true.

But it is 1931. Is this the literature the world needs? Wilson doesn't use the phrase art for art's sake, but maybe art should also be a bit for society's sake? He says Valéry's and Eliot's criticism is engaged in 'an impossible attempt to make aesthetic values independent of all other values.' He finds The Vision--Yeats' attempt to create a universalizing set of symbols--unserious and unhelpful, not to metion Yeats' experiments in automatic writing. He quotes disapprovingly, twice I think, Eliot's declaration from his essay 'For Lancelot Andrewes', that he is "a classicist in literature, an Anglo-Catholic in religion, and a royalist in politics." Wilson is distinctly none of those things.

I also found this on Valéry amusing:

"...one cannot help rebelling against what appears to be Valéry's assumption that it is impossible to be profound and to write as lightly and lucidly as [Anatole] France did."

A goal I suspect dear to Wilson's heart...

After the crash on Wall Street in 1929, Wilson was drawn to Communist ideas, though never becoming an actual Communist. But he did travel to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1935; once there he was put off by the increasingly totalitarian atmosphere, and certainly would have nothing to do with the Soviet Realist idea of art for politics' sake. Wilson doesn't fully construct his middle ground in this, and probably it can't be precisely defined. But technique matters and engagement matters, too. For that the book is applicable now as well, but maybe that's a perennial question. I do find it a very great work of criticism.

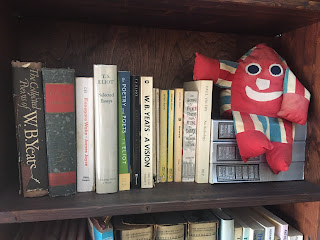

And one I tried to read before...at some point in my 20s I started this, but the only authors I'd then read were Yeats (whom I didn't know well) and Eliot (whom I knew only a little better). I thought, well, before I read this, I should read some of these authors. Now, (ahem) a few years later..., it was time to try again. One of Karen's categories this year was 'Classic on your TBR the longest'. Is this absolutely the one? I don't know, but it's been there a long time...

|

| "What!" says Humpty, "I need to read all those books just to read the one?" Well...maybe not entirely... |