"For readers who hope to be entertained by description of adventures, or for those want to be enriched by reports of the success and various detours of a contemporary, I hope my story will suffice. After all, this contemporary was part of the first eight decades of the twentieth century."

-Vienna, March 8, 1979

"...one of the ten best architects of the twentieth century."

-Time Magazine

On the way to acquiring that title, there were indeed some adventures. Gruen was born to an upper middle class family in Vienna; his father was a lawyer. They were assimilated Jews, not practicing. (Gruen says he was in synagogue only for the weddings of family friends.) In 1918, at the end of the war, his father died of the Spanish Flu. Austria in general, and the Gruens in particular, were impoverished.

Gruen had always been interested in architecture, but with no money for education, he apprentices himself as what seems to be basically a bricklayer. At the same time (this is the 1920s) he organizes a left-wing (Socialist) cabaret for which he functions as the MC. He wangles a year at a university architecture department, but the anti-Semitism as well as what he considers the lack of imagination on the part of the teachers keeps him from completing a degree.

The cabaret is squelched with the rise of Austrofascism (Gruen calls it a 'dictatorship tempered by sloppiness') when Dollfuss becomes Premier in 1932. Still Gruen is managing some more architectural commissions, most notably shop fronts, and has nearly qualified as an official architect by means of experience and exams. But it's now 1938, and when in March Karl Schuschnigg says the Austrian military will not resist should the German army force Anschluss, Gruen realizes he has to be ready to run at a moment's notice.

This is the moment of the 'description of adventures' Gruen promised in the introduction (quoted above). US immigration law required an affidavit from a US resident, with a promise of financial support, to acquire a visa to enter the US at the time. Gruen had an uncle who'd emigrated to the US in 1914, but the uncle, while well-meaning, was still impoverished. But Gruen had made friends with a woman, Ruth Yorke, who'd come to Austria to learn German in the 20s. She became a star on a radio soap opera, and had rich friends; one of them agrees to become Gruen's sponsor. He gets the necessary exit visa, now a German one, and the required transit visas: his plan is to travel via Switzerland, France, and the UK. (Anna Seghers' Transit covers some of the same visa complications.) But when he's about to go, he learns that the Gestapo has occupied his apartment in his absence, and he's advised not to go home. But everything he needs to leave is still there.

Earlier a non-Jewish friend had told him that he was joining the Nazi party to keep his job, but that he was still a friend and if Gruen ever needed any help... So Gruen calls up this friend and explains the situation. A few hours later the friend shows up in a Storm Trooper uniform--Gruen is terrified--but he has the luggage and visas and tells him to go, go, go. It's only after the war, when he meets this friend again in Austria, that he learns the story: his friend had stolen a uniform, shown up at the Gruen apartment, and said, These are the belongings of the Jew Viktor Grünbaum and henceforth confiscated, carrying them all away.

The story even has an amusing (?) denouement: this friend was labeled politically unreliable for this, was immediately drafted into the German army, and sent to various dangerous fronts. Promotions to officer class were refused for him. Still, he survived. At the end of the war, when the Russians occupied Vienna, he was arrested as a Nazi, but was able to prove that, though he had been a Nazi, he was also politically unreliable, and so was let go.

Anyway, those were the thrills...now we're on to the successes and various detours. 😉

Actually, maybe a moment about the story of the book. Gruen did have an interesting life, wrote some works about architecture and city planning over the course of his professional career, and later in life, various people told him, you should write an autobiography. He wasn't especially interested, he says, made a few half-hearted stabs at it, but then his doctor told him he was near the end, and he took it more seriously. This is the book. It was originally written in German, but this English translation is from 2017. It's pretty finished, but wasn't published during his lifetime, and it's a bit imbalanced. It's clear the thrilling parts engaged him more. He writes about the first several projects that got him established in the US, but he doesn't say much about his professional career after about 1956. Instead he discusses a few failures: a plan to make central core of Fort Worth pedestrian-only, his plan for a residential development on the old Newhall Ranch in Valencia, California, (Suburban L.A.), and a plan to revitalize Teheran that collapsed when the Shah was deposed. (Though it was already going south before that.) The last third of the book discusses his idea of environmentally-oriented city planning: pedestrian-only downtown cores; electric trams and subways; but massive parking garages on a ring road that surrounds that core. After his part finishes, there's a couple of reminiscences by his children, and a rather annoyingly theoretical (Walter Benjamin! Gilles Deleuze!) afterword by the translator, who is an Austrian academic.

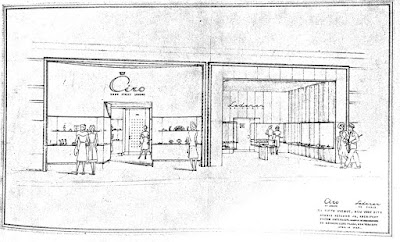

He started in the US, with changes to shop fronts to invite browsing:

These were on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Lederer, of the store on the right, was also a Jewish emigrant from Vienna.

He came up with the idea for what would be a shopping mall--a pedestrian shopping center--during World War II, but it couldn't be built then. But he keeps the idea in mind for after the war. His first completed was for the owner of Hudson's, then the major department store in Detroit (and the second largest in the country); they built the Northland Mall in suburban Detroit, completed in 1956. His second, for the Dayton family, owners of the large department store of Minneapolis, was the completely enclosed Southdale Center, the first of its kind. This the maquette for it:

The raised access roads were for buses to get to the center. The interior was meant to be walkable and inviting; while this wasn't his vision, it seems obvious to me in retrospect that the acres of parking around it would inevitably lead to its being isolated from the community. But maybe he can't be blamed for the outcome? In any case he recognized the subsequent negative aspects of what he'd initially designed and had hoped for something different.

His idea of his relationship to his clients:

I was a bit surprised when he quoted from an early article by Jane Jacobs that praised his Detroit mall; I would have thought she would have objected. I wondered if she later changed her mind on Gruen, and I looked him up in the index of The Death and Life of Great American Cities of 1961 (A wonderful book! Read it if you care about US cities.) and he's there, but she's still quite impressed, and discusses his Fort Worth plan at considerable length. If you know the Jacobs, you'll know she's quite capable of doing down city planners she doesn't like. (Robert Moses, Lewis Mumford.)

Anyway, an interesting book about which I've gone on long enough...Though his second wife, Elsie Krummeck, was pretty fascinating in her own right: his business partner until they divorced, a talented designer in her own right, mother of his two children, and I could have devoted more space to her.

A couple of quotes:

[From a description of his Matura thesis]: "I argued that Faust could have saved his soul with a grand vision of liveable homes on land reclaimed from the sea. The idea was a little far-fetched, I now admit."

"They could not believe a Californian would take a train instead of a car." [In regard to the Valencia project--whoever 'they' were, they may have been right.]

"The mass use of individual transport machines [cars] within a collective is an absurdity, a life-endangering breach of all the values of a city. It means that all citizens may also insist on possessing their own wells, septic tanks, rifles." [Though it is the US: all citizens may insist on possessing their own rifles...]

Anyway, born in Vienna, he lived there until he was 35; later in his life when he was a successful architect, he had an international practice with homes in L.A. and New York, but he also had a place once again in Vienna, where he primarily lived after he retired at the age of 65. So I'm calling it the Austria book for my European Reading Challenge:

I first saw the book mentioned here which has more information.

Interesting post--Walter Benjamin crack aside!--about a person I'd never heard about before. That anecdote about the fake SS friend and his survival despite being sent to various WWII fronts as punishment for his sympathies was quite incredible. Truth is stranger than fiction & etc.

ReplyDeleteI must have heard of him before--he's in Jacobs--but the name hadn't really registered. A fascinating life.

DeleteI actually like Benjamin pretty well--I've never read any Deleuze--but I'm suspicious of academics who now feel a need to bring him in for what I feel are generally thin reasons. Though to be fair, it's the Arcades Project materials that Baldauf cites, clearly appropriate, and she's far from the most impenetrable of 'Theory' types.