O, it was out by DonnycarneyWhen the bat flew from tree to treeMy love and I did walk together;And sweet were the words she said to me.Along with us the summer windWent murmuring--O, happily!--But softer than the breath of summerWas the kiss she gave to me.

Thursday, March 30, 2023

Joyce (#poem)

Wednesday, March 29, 2023

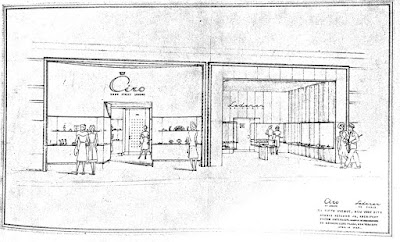

Victor Gruen's Shopping Town

"For readers who hope to be entertained by description of adventures, or for those want to be enriched by reports of the success and various detours of a contemporary, I hope my story will suffice. After all, this contemporary was part of the first eight decades of the twentieth century."

-Vienna, March 8, 1979

"...one of the ten best architects of the twentieth century."

-Time Magazine

[From a description of his Matura thesis]: "I argued that Faust could have saved his soul with a grand vision of liveable homes on land reclaimed from the sea. The idea was a little far-fetched, I now admit."

"They could not believe a Californian would take a train instead of a car." [In regard to the Valencia project--whoever 'they' were, they may have been right.]

"The mass use of individual transport machines [cars] within a collective is an absurdity, a life-endangering breach of all the values of a city. It means that all citizens may also insist on possessing their own wells, septic tanks, rifles." [Though it is the US: all citizens may insist on possessing their own rifles...]

Anyway, born in Vienna, he lived there until he was 35; later in his life when he was a successful architect, he had an international practice with homes in L.A. and New York, but he also had a place once again in Vienna, where he primarily lived after he retired at the age of 65. So I'm calling it the Austria book for my European Reading Challenge:

Thursday, March 23, 2023

Denial (#poem, #Dewithon2023)

Denial

When my devotions could not pierceThy silent ears;Then was my heart broken, as was my verse:My breast was full of fearsAnd disorder:My best thoughts, like a brittle bow,Did fly asunder:Each took his way; some would to pleasures go,Some to the wars and thunderOf alarms.As good go any where, they say,As to benumbBoth knees and heart, in crying night and dayCome, come, my God, O come,But no hearing.O that thou shouldst give dust a tongueTo cry to thee,And then not hear it crying! all day longMy heart was in my knee,But no hearing.Therefore my soul lay out of sight,Untun'd, unstrung:My feeble spirit, unable to look rightLike a nipt blossom, hungDiscontented.O cheer and tune my heartless breast,Defer no time;That so thy favours granting my request,They and my mind may chime,And mend my rhyme.

Sunday, March 19, 2023

Sunday Salon (and CCSpin Number Reveal!)

Last Week

Posted Chicago poet Keith Preston on 'Reading in Bed As A Fine Art'.

Blogged about Samuel Butler's The Way of All Flesh, a book from my Classics Club list.

And signed up for the latest Classics Club spin #33. The spin number is 18,

The mind's a shortchangingHuckster with a craftyWife and FiveScoundrel children.

It won't change its ways.The mind's a knot, says Kabir,Not easy to untie.

|

| Chocolate Pots-de-créme, all gone now sadly... |

Thursday, March 16, 2023

Reading In Bed As A Fine Art (#poem)

That reading in bed is a rite with a ritual,Those couch-cognoscenti our essayists teach;Ye novices, learn from us aesthetes habitualThe bed written rules that the essayists preach.Retire to your room with the paraphernalia,Some hoary old volume, your brier and pouch,And garbing yourself in nocturnal regalia,Then kindle the candle that stands by the couch.For bed books, no new books we essayists handle;For night lights, no bright lights are known to the game—A second-hand book by a flickering candle,A tattered old tome by a tremulous flame.We cling to the candle, so human, appealing;It weeps as it works, shedding tallowy tears;So second-hand books touch us readers of feelingWith lachrymose thoughts of delectable years.How fondly we dandle in candle-lit darknessFair folios veiled in voluptuous vellum,And thrill to the mad Latin grammar of HarknessOr rakish old Caesar's wild Gallicum Bellum.How dull and drab novels or newspaper colyums!Ye tyros, give ear to us urging insteadThe old broken volumes, the vellum-bound volumes,The worm-eaten volumes we lug to our bed.

Wednesday, March 15, 2023

Classics Club Spin #33

How can you not spin for #33? I feel like I should add a 1/3rd to that.

I'm nearing the end of my original list; the last couple of spins I added a few books from a potential new classics club list. But not this time! I'm concentrating on knocking off those remaining books, so there will be some doubling up.

(For full directions on how to do a Classics Club spin, see the organizing post. But you know all that...)

The First Five

Samuel Butler's The Way of All Flesh

That's said of our hero, Ernest Pontifex. He's got some growing up to do."Embryo minds, like embryo bodies, pass through a number of strange metamorphoses before they adopt their final shape."

"I may very likely be condemning myself, all the time I am writing this book, for I know that whether I like it or no I am portraying myself more surely than I am portraying any of the characters whom I set before the reader."

Ernest first appears on the scene for his baptism, which is...funny? His grandfather:

"'Gelstrap,' he said solemnly, 'I want to go down into the cellar.'Then Gelstrap preceded him with a candle, and he went into the inner vault where he kept his choicest vintages.He passed many bins: there was 1803 Port, 1792 Imperial Tokay, 1800 Claret, 1812 Sherry, these and many others were passed...[then] a single pint bottle. This was the object of Mr. Pontifex's search.Gelstrap had often pondered over this bottle. It had been placed there by Mr. Pontifex about a dozen years previously...the last chance of securing even a sip of the contents was about to be removed for ever..."

"...Ernest could not be expected to know this; embryos never do."

"He had, in fact, to burn his house down to get his roast suckling pig."

"They would have been equally horrified at seeing the Christian religion doubted, as at seeing it practiced."

"Christianity was true in so far as it had favoured beauty."

"Ernest could never stand being spoken to in this way by his mother, for he still believed that she loved him."

"A man first quarrels with his father about three quarters of a year before he was born."

Butler is particularly hard on familial relations, and at times I was irritated by how much he stacked the deck against Ernest's parents. Theobald and Cristina are self-righteous hypocrites. Still Butler over-generalizes a bit. I dunno: there are bad families out there. But I rather liked my parents...

Still:

"It was the system rather than the people that were at fault."

I was amused to discover via Wikipedia that the Dr. Skinner of Ernest's prep school (Roughborough in the novel; Shrewsbury School in real life) was the Dr. Benjamin Hall Kennedy of Kennedy's Latin Primer. Still at least sometimes in use, and that's my copy I've taken a photo of. The Dr. Skinner of the novel is portrayed as not very loveable...

All in all, though, a pretty great novel, I thought, even if slow to start. Overton's ironic and knowing telling keeps it moving along pretty well. "It happens that a faithful rendering of contemporary life is the very quality which gives its most permanent interest to any work of fiction,..." Sure. But a little irony doesn't hurt either.

One of the novels on that Modern Library list of the greatest English language novels of the 20th Century, and one off my Classics Club list...

Thursday, March 9, 2023

There Are Roughly Zones (#poem)

There Are Roughly Zones

We sit indoors and talk of the cold outside.And every gust that gathers strength and heavesIs a threat to the house. But the house has long been tried.We think of the tree. If it never again has leaves,We'll know, we say, that this is the day it died.It is very far north, we admit, to have brought the peach.What comes over a man, is it soul or mind--That to no limits he can stay confined?You would say his ambition was to extend the reachClear to the Arctic of every living kind.Why is his nature forever so hard to teachThat though there is no fixed line between wrong and right,There are roughly zones whose laws must be obeyed?There is nothing much we can do for the tree tonight,But we can't help feeling more than a little betrayedThat the northwest wind should rise to such a heightJust when the cold went down so many below.The tree has no leaves and may never have them again.We must wait till some months hence in the spring to know.But if it destined never again to grow,It can blame this limitless trait in the hearts of men.

Sunday, March 5, 2023

Sunday Salon

Last Week

Put up a poem by Emily Henrietta Hickey which I've always liked.

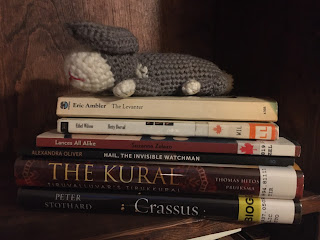

Blogged about Eric Ambler's The Levanter, a spy novel. Pretty good, but not one of his best.

The rest of the reading week:

Thursday, March 2, 2023

The Ship from Tirnanoge

The Ship from Tirnanoge

We two were alone by the sea:

I and the man I loved with me.

Our eyes were glad and our hearts beat high,

As we sat by the sea, my love and I;

Till we looked afar, and saw a ship:

Then white, white grew his ruddy lip;

And strange, strange grew his eyes that saw

Into the heart of some deep awe.

His hand that held this hand of mine

Never a token gave, nor sign;

But lay as a babe's that is just dead:

And I sat still and wondered.

Nearer and nearer the white ship drew:

Who was her captain, whence her crew?

Her crew were men and women bright,

With fair eyes full of unknown light.

From far-off Tirnanoge they came,

Where they had heard my true-love's name:

The name the birds and waves had sung

Of one that must bide for ever young.

Strong white arms let down the boat;

Song rose up from many a throat.

Glad they were who soon had won

A lovely new companion.

They lowered the boat and they entered her;

And rowed to meet their passenger:

Rowed to the tune of a music strange,

That told of joy at the heart of change.

I heard her keel on the pebbles gride,

And she waited there till the turn o' the tide;

While they kept singing, singing clear

A song that was passing sweet to hear:

A song that bound me in a chain

Away from any thought of pain.

They paused at last in their sweet singing,

And I saw their hands were beckoning,

In a rhythm as sweet as the stilled songs,

That passed to the air from their silent tongues.

He rose and kissed me on the face,

And left me sitting in my place,

Quiet, quiet, life and limb,

I, who was not called like him.

Into the boat he entered grave,

And the tide turned, and she rode the wave;

And I saw him sitting at the prow,

With a rose-light about his brow.

The boat drew nigh the ship again,

With all its lovely women and men.

I saw him enter the ship and stand,

His hand held in the captain's hand.

The captain wonderful to see

With eyes a-change in depth and blee;

A-change, a-change for ever and aye,

Blue, and purple, and black, and gray;

And hair like the weed that finds a home

In the depth of a trail of white sea-foam.

I wist he was no mortal man,

But he whose name is Manannan.

They sailed away, they sailed away,

Out of the day, into the day.

.jpg)