Three complicated chunksters all of which I started long posts for. Those posts didn't get finished. (Oh, well.) Time to clear the decks.

Heimito von Doderer's The Strudlhof Steps (850 pages)

This is a fairly new release from New York Review Books, and Vincent Kling won the most recent

Wolff Prize for translation from the German for it. The novel came out in 1951 in German, and hasn't previously appeared in an English translation.

The main events take place just before and just after World War I in Vienna. I'm a sucker for the place and time. And, hey, it's shorter than

The Man Without Qualities; as a bonus, von Doderer finished it, too

. Four sections, each coming to a dramatic climax--who gets married, who gets dumped, who gets a leg cut off by a tram--generally on or near the Strudlhof

Steps:

Lt. Melzer features in the subtitle. He likes to drink Turkish coffee on the skin of a bear he shot in Bosnia in 1912; watched his commanding officer (whom he likes) die on the Italian front in World War I; seems almost unmarriageable, but is he?

René von Stengeler is born into a wealthy Protestant family, captured by the Russians in 1916, only making it back to Vienna after the war is over. Does he marry Grete, back from Oslo where she escaped the misery of post-war Vienna by teaching piano? And why does René's sister commit suicide? Because we know she did from the first few pages.

The novel requires tolerance, but pays back. It moves back and forth in time, at first seemingly arbitrarily. You have to accept its terms, and give it space to get started. Characters have last names or first names but not necessarily both, and sometimes merely initials. For example, we never learn Lt. Melzer's (a major character) first name: on page 823, "Sorry, but we don't know Melzer's first name." The narrative voice has a curious diffidence.

Von Doderer's politics were not particularly admirable. He joined the Nazis in the mid-30s, when the party was illegal in Austria. The afterword, by Daniel Kehlmann, says he was quite anti-Semitic at that time. He later turned against the party, but never publicly, and as a WWI veteran, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht, serving in garrison duty, first in Norway, later in France, where he started writing this novel. The publication of the novel was delayed while von Doderer was de-Nazified. René von Stengeler is clearly a self-portrait, and deliberately not a flattering one. What did he think by 1950? I don't know. There are minor Jewish characters in this, and they're treated with real sympathy.

Anyway, I thought it was very good.

William Faulkner's Light in August (480 pages)

I had heard that Light in August was a murder story, the story of Joe Christmas, and, well, it is. Christmas (named for the day his infant form was dropped off at the orphanage) murders his lover. Christmas may have black blood--he doesn't know and we don't know either, but he thinks he does, and though he could pass for white, once he's accused of having a drop of black blood (by his own grandfather, no less) he assumes he does.

But Christmas' story is not the whole of the novel by any means. It's the portrait of a town called Jefferson, and not just the evils of racism, but also the ways racism distorts the life of the town. Nowadays we don't really have any problem contemplating that Jefferson the man may have been a bit racist, but the novel came out in 1932. There's a daring irony to that. Was Faulkner in his heart of hearts free of racism? Certainly not, and I doubt he would say he was. But he knew that problem for a problem, and that counts for something. Percy Grimm, the white captain of the National Guard, is a particularly (dare I say it?) grim portrait of a racist.

And am I the only one who doubted Christmas committed the murder? No, because the Wikipedia

article says it's unclear who did it. I don't think that's actually sustainable, and that Christmas really did do it, but I did wonder during the middle of the novel. But maybe that's attributable to too many years of reading mysteries: the obvious suspect is never the culprit.

The town's a mess, and there's nothing to do but escape, but almost nobody does; the only ones who do are Lena Grove and Byron Bunch, running off in a folie à deux: she's looking for the man who got her pregnant and who will never marry her, and Byron's hoping she'll settle for him instead, and meanwhile he'll be there when she (which she won't) changes her mind.

One other thing to be said about this is that, of the great Faulkner novels, I thought this was the easiest read. And that's definitely something... 😉 It's easier than The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, and Absalom, Absalom. No chapters from the POV of dead people or madmen. Not the greatest of that quartet, I'd say, which for my money is Absalom, Absalom, but a better starting point. (Though if you include Sanctuary in your list of top Faulkner, I would say that one's a pretty straightforward read.)

Gershom Scholem's Sabbatai Sevi (929 pages, plus bibliography, notes and index)

Sabbatai Sevi (1626? - 1676) declared himself the Jewish messiah in 1665. (He may have intimated it as early as 1648 but only in limited circles.) Gershom Scholem, Jewish historian and friend of Walter Benjamin, made Sevi the subject of a major book.

Sevi (there should be a dot under the S which I can't figure out how to type, but think Tsevi or Zevi) was born in Smyrna to a middle-class merchant family, studied the Kabbala in Jerusalem, traveled on religious business to the Jewish community in Egypt and later to Constantinople. All lands under the control of the Ottomans at the time. When he began his mission in earnest, Nathan of Gaza was his prophet and explicated the theology of the new movement. Scholem, as a historian of Jewish mysticism, is rather more taken with Nathan than Sevi.

But the stories of Sevi and Nathan are just a small part of this fascinating book. What's surprising is the Europe-wide discussion of these figures, and not just in the Jewish community. Italy, Amsterdam, Morocco, Poland, Hamburg, Egypt are all discussing this new Messiah. English chiliastic Protestants write books about Sevi, who, they think, will lead 10000 Jews from the Lost Tribes across the River

Sambatyon, armed with bows and arrows but still invincible. (The River Sambatyon doesn't actually exist, which is why you haven't heard of it.) Samuel Pepys writes about Sevi in his diary! Along with all the women he was shagging. He features in Venetian ambassador's reports and Jesuit Relations. One can imagine Blaise Pascal, roughly contemporary, being discussed across Europe, but it turns out not all Europe-wide discussions were so scientific.

Sevi himself always advocated a peaceful movement. Faith and the perfection of the self would lead to the kingdom of God. There were no armies in his vision.

In fact, I found the reception of Sabbatai Sevi to be more interesting than the biography of Sevi himself. Scholem is inclined to attribute Sevi's messianic proclamations to mental illness, labeling him a manic-depressive. Maybe. But diagnosing mental illness in the present is difficult enough--DSM-III, DSM-IV, DSM-V have different labels, and so will DSM-XCIII--diagnosing it in figures in the past in inherently suspect.

Why could a Messianic movement take root then? Scholem finds the main factor to be the diffusion of Kabbalistic thinking going back to Isaac Luria (1534-1572). But also the Jewish massacres by Khmelnitsky in Poland and the Ukraine take place in 1648. As for the interest in Christian circles, there was a feeling that 1666 should be an important year: the number of the beast plus 1000.

Once in Constantinople, Sevi was arrested by the Ottomans. They were relatively

tolerant of Judaism, but weren't prepared to tolerate a figure who was going to lead an army of invincible Jews and put the crown of the world on his head. (If, in fact, Sevi intended these things. Probably not.) He seems to have impressed the vizier and then later the sultan, but still in September of 1666, he was told to convert to Islam or die. Sevi converted.

Surprisingly this wasn't the end of the movement. A number of Sevi's followers also converted over the years. Sevi was ordered to leave Constantinople, first to Edirne, which was at times the Ottoman capital, then later to Albania. Sevi led his converts, the Dönmeh, also referred to as the Ma'min, or the Faithful, in a new syncretistic religious community influenced both by Judaism and Islam, particularly that of the mystical Sufi orders. Scholem's book ends in 1676, when Sevi dies, but the community survived, centred in Salonica until the Greek-Turkish population transfers of 1922. The Dönmeh were often thought to be hidden Jews, but they were Muslim enough for the time, so they had to go. The story of the Dönmeh would be fascinating, and Scholem had intended to write a book, but didn't live to do so. They do feature in Mark Mazower's book (recommended!) on Salonica, though.

I read the second edition of the book, which came out in 1973, translated by R. J. Zwi Werblowsky. Scholem says in the introduction that he had access to more material by then, and that it superseded the earlier edition.

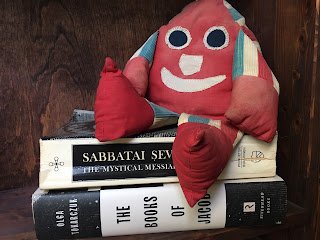

And why did I read this book now? Well. Did I really need to read one nine-hundred page book about a failed Jewish messiah in order to prepare for another nine-hundred page book about a failed Jewish messiah? Oh, probably not, but that's what I did:

These were all August reads for me, and it's been a while now. Still I wanted to review these because they knock off a couple of challenge items.

Light in August was on my original Classics Club

list and works for this year's Back to the Classics

challenge.

And the other two count for this year's European Reading

Challenge:

The Strudlhof Steps is clearly an Austrian book, though it does have scenes in Norway and Switzerland. Sabbatai Sevi spent most of his life in what is now Turkey, but I've already done Turkey this year. Sabbatai Sevi the book ranges across Europe. Still we'll stick Sevi himself, who spent the last eight years of his life in Ulcinje, which was in the Ottoman province of Albania at the time, but is now in Montenegro.

Short reviews, did I say? Well, short-ish...