Well, I squeezed in one last book review just yesterday, but there will be no more squeezing in, and my bookish travels in Europe are done for the year. The final list:

Well, I squeezed in one last book review just yesterday, but there will be no more squeezing in, and my bookish travels in Europe are done for the year. The final list:

Adina is a schoolteacher in the late years of Communist Romania. Her circle of friends include Paul, a musician, and Clara, who works in a factory. Paul's band gets in trouble with the secret police because some apparatchik thinks their latest song is about the dictator Ceauşescu, and so Paul, even though he's not the lyricist, ends up in trouble dragging down Adina and the others."Where does it come from, he asked, this sympathy?"

I thought this was good, but I was more impressed by The Land of Green Plums (1994 in German). I felt the characters were better differentiated in that novel, which made the choices feel more poignant. This is a shorter book, only 220 pages, with fairly large margins, practically a novella in length. The opening started with quite a lot of folkloric elements: gypsies who are afraid of hares, the tooth fairy, who's a mouse in Romania, it seems:

"Mouse O mouse bring me a brand new toothand you can have my old one."

"...if what young people do in the name of love should be called a sin..." [435]...then this is is not the book for you.

"Now, since the reason we are here is to enjoy ourselves and have some fun,..." [715]

|

| Lauretta, as imagined by Jules Lefebvre |

"a friar who was, without doubt, some gluttonous soup-swilling pie muncher" [259]

"Nothing will seem long to those who read in order to pass the time." [858]

Guilt

At first, like a head cold--then, three glasses of wine--no five.Hour twelve, a low-grade fever. Hour fourteen, your whole body ison fire --each joint snaps open, heat coiled inside your knees. A reaction tothe measles booster, days before the trip. Fades like a hangover,then rearsits host of heads again. We chose notto go to Chișinău -- We have no businessbeing here anymore. Reroute to Iași. It's the heat,driving stick, a last hiss,writing to the chief rabbiI'm sorry we're not going to make it--the GPS, the roads, Russian, the carwhich really meansI'm sorry we are afraid

-Leah Horlick

I've never had a measles booster, but I had the shingles one not too long ago. That's about how it was.

In your right hand, take the ten-hour tourist visa. Form a window withyour left, frame the last functioning hammer and sickle flag. Walk sixtimes around the last twenty thousandtonnes of Soviet ammunition. A tanker spills cigarettes out of its sidelike a whale and so we say May the memory of this whale be a blessing.Wash your hands before you dunk your headbeneath the x-ray at the checkpoint, the x-ray that pretends not to noticeyou. Rabbi, is therea blessing for the border?A blessing for the border--May God bless and keep the borders, seen and unseen, far away from us.

-Leah Horlick

Transnistria is that breakaway region in Moldova (across the Dniester River) that's propped up by Russia.

She says in an afterword she lifted that final line from Fiddler on the Roof, but I knew that. 😉("Is there a proper blessing for the Tsar?" "May God bless and keep the Tsar...far away from us.")

The title poem is probably the best, but too long to quote. Interesting stuff.

That's the opening line of Who Pays the Piper? and it's Lucas Dale who ends up dead. He didn't get what he wanted that time! (And ever is such hubris rewarded?)"I always get what I want," said Lucas Dale.

"He had three daughters of his own, and was sometimes put to it to conceal a most obstinate softness of heart where girls were concerned."

|

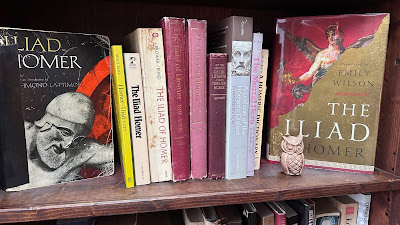

| Erechtheum the Owl says, This is important stuff. Get obsessed! |

Let Hector turn the Greeks around againand make them panic, lose their will to fight,and run away until at last they fallamid the mighty galleys of Achilles,the son of Peleus. He will send forthhis friend Patroclus, who will slaughter many,including my own noble son, Sarpedon.Then glorious Hector, out in front of Troy,will kill Patroclus with his spear, and then,enraged at this, Achilles will kill Hector.And after that has happened, I shall causethe Greeks to drive the Trojans from the ships,and force them to retreat continuouslyuntil, through great Athena's strategies,the Greeks have seized the lofty town of Troy.Until that time, my anger will not cease.

Then Hector understood inside his heart,and said, "The gods have called me to my death,I thought Deiphobus was at my side.But he is on the wall. Athena tricked me.The horror of my death is near me now,not far away, and there is no way out."

After the mound was built, they went back home,then came together for a glorious banquetinside divine King Priam's house. And sothey held the funeral for horse-lord Hector.

"...the translator of Homer should above all be penetrated by a sense of four qualities of his author;--that he is eminently rapid; that he is eminently plain and direct, both in the evolution of his thought and in the expression of it, that is both in his syntax and his words; that he is plain and direct in the substance of his thought, that is, in his matter and ideas; and, finally, that he is eminently noble;..."

And Hektor knew the truth inside his heart, and spoke aloud:"No use. Here at last the gods have summoned me deathward.I thought Deiphobus the hero was here close beside me,but he is behind the wall and it was Athena cheating me,and now evil death is close to me, and no longer far away,and there is no way out.

Such was their burial of Hektor, breaker of horses.

The earth grew black behind them as if plowed,though it was made of gold. It was amazing.

Speak up! Do notconceal your thoughts. We ought to share our knowledge.

Tell me, do not hide it in your mind, and so we shall both know.

Tell me about a complicated man

Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath