"We shall never be again as we were!"

Four young people and their watchful elders, first in London, briefly in Switzerland, and for most of the last third of the book, in Venice, where there's a death.

Kate Croy, the 'handsome girl', starts us off. She's maybe 25, has £200 a year from her late mother's estate, though she gives half of that to help her widowed (and impoverished and ungrateful) elder sister with four kids. Our first scene shows her hunting up her scoundrelly father and proposing to move in with him. Her father's a bankrupt and has done something (?) that makes him unpresentable in society. Still, she prefers him to her controlling aunt. But he refuses her, because if she can squeeze money out of the rich aunt maybe some of it will drift on to Pops. Why does she not want to live with Aunt Maud? Is it because Kate's in love with somebody inappropriate? Well, yes, she is.

Merton Densher, a 'bland Hermes' according to Henry James himself in The Art of the Novel, seems like a nice enough guy. He has a respectable job as a journalist, but does not come from money, does not have money, and, then as now, as a journalist, does not have much prospect of acquiring money. But he's definitely in love with Kate, and though the coy Croy generally hides it, she's in love with him. £200 a year, even £100 a year, plus the income of a steady job, oughtn't be so difficult, but Kate wants more, and then Aunt Maud does have money. But will Aunt Maud fork over or does she have other plans? Ah, she has other plans.

Meet Lord Mark. ("...he was, oh, yes, adequately human.") Mark's a pretty minor lord, and doesn't have any money himself, but he is a Lord, and Aunt Maud has more than enough money, and Maud's determined to propel Kate (and presumably herself, by connection) into aristocratic circles. If Kate wants to live with adult protection, and not in her sister's Chelsea hovel. she's going to have to entertain and encourage any overtures Lord Mark might make.

(I've been to Chelsea. Not hovels no more.) It is amusing that Chelsea means hovels to the Londoner Kate, but for our next character, the American, it means Carlyle. (Well, I'm an American, of sorts, too.)

Introduce into this circle Milly Theale, in her early 20s, an American orphan from New York, rich beyond any European's furthest imaginings. She's traveling about Europe (Switzerland at first) with her older companion, Susan Stringham, a writer from Burlington, Vermont, 'which she boldly upheld as the real heart of New England, Boston being "too far south"'. We learn almost right away that Milly had been sick in the States before she started traveling, and it's not giving too much away--it's the one thing I was sure of before I read the novel--that it's her death (in Venice) that provides the climax.

(Boston is not too far south to be the heart of New England.)

Milly decides to go to London where Susan's old school friend Maud lives.

In Lord Mark's family estates there's a Bronzino portrait of a young woman, whom everyone says looks exactly like Milly Theale. And maybe the woman looks rather ill? Anyway, Milly has a fainting fit when she sees the portrait. The internets agree the portrait James intends is that of

Lucrezia Panciatichi, so you can imagine that's our American heroine above on the left.

Sir Luke Strett, a noted London doctor and surgeon, shows up to look after Milly, though everyone pretends he's just a great friend.

You can see the outlines of a plot taking shape and I don't want to give away too much; as I said, I didn't know how it would go exactly myself--I have not (yet) seen any movie version--and while this is one of those novels much discussed--it's a major example in Sontag's Illness as Metaphor--it may be possible to come to it naively, as original readers did. And as I mostly did. There is suspense, surprising perhaps... 😉 in late James, and I'll leave it there. Though I can say, as a good friend of mine frequently does, it's all about the money. Well, almost all.

It is late James, and I have occasionally snarked about that prose style before. Here's an example from around halfway through the novel. Merton Densher is back in London; he's been away in New York, working, where he had met Milly. (From Book VI, Chapter 5, near the beginning)

"She [Milly] had been interesting enough without them [Kate and Aunt Maud]--that appeared to-day to come back to him; and, admirable and beautiful as was the charitable zeal of the two ladies, it might easily have nipped in the bud the germs of a friendship inevitably limited but still perfectly open to him."

This is Merton thinking, but yet it isn't Merton. We'll set aside that nobody thinks in such rounded phrases because everybody does that in James. One of those 'two ladies' is Kate, with whom Merton is more or less secretly engaged. Would he think of her as just one of 'two ladies'? And 'admirable and beautiful' and 'full of charitable zeal', Aunt Maud is not, and Merton knows it perfectly well, since she's the reason he and Kate are keeping their engagement secret. As well as the fact that Aunt Maud's zeal is about pimping Milly on the social circuit for societal advantage. (We'll come to have our doubts about Kate, too.) As for that 'friendship inevitably limited but still perfectly open', well, it's limited by that secret engagement, but Milly's already half in love with Merton (though it's not clear how well Merton understands that at this point) and 'friendship' and 'perfectly open' mean very different things to Milly and to Merton.

So James is ironically complicating our relationship with the characters in ways we have to work out to get there, while at the same time sounding like 'Everything is Awesome.' (Cue that Lego movie song

here...)

It must be said that James knows:

"'Then what,' he demanded, frankly mystified now, "are we talking about?"

That's Merton Densher.

I don't know if Thom Gunn was thinking of

The Wings of the Dove when he wrote this couplet/quip, but he very well could have been. (Though it would apply to other late books as well.)

Jamesian

Their relationship consisted

In discussing if it existed.

It also struck me how close in theme this was to The Ambassadors, James' novel of the next year (1903). It's Lambert Strether from that novel who advises, "Live all you can, it's a mistake not to," a statement also deeply ironic. It could have fit into this one. Sir Luke Strett to Milly:

"My dear young lady, isn't 'to live' exactly what I'm trying to persuade you to do?"

I reread Susan Sontag's Illness as Metaphor now that I've read The Wings of the Dove, (well, the Sontag at least is short) and I do think she's a little hard on James, whose irony complicates everything, but, of course, Sontag's basic point is correct: a will to live might help Milly, but what she really needs is antibiotics, and putting too much emphasis on her will feels like blaming the victim. (Way oversimplifying Sontag here.)

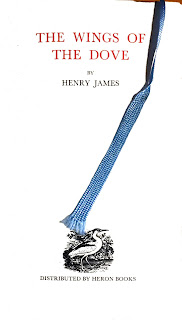

I'll leave you with a picture of the

Palazzo Barbaro in Venice, which becomes the Palazzo Leporelli in the novel, rented by Milly as her (modest) domicile when she was there. I understand it's used as the set for scenes in the movie version with Helena Bonham Carter. James used a writing desk still there to compose

The Aspern Papers.

It was my spin book. (I somehow had it in my head the spin ran to the 31st. Oh, well.) It is late James, with all the noodliness that implies, but I quite liked it, after having

dreaded it a bit, and I think it's replaced

The Ambassadors as my favorite of that period.

If you've read it, what did you think? Are our couple actually redeemed? What, in fact, do you think was their final decision? (Because, of course, it ends without entirely telling you, as I, too, am now doing...)