Well, I don't think I need to say what the world of The Handmaid's Tale looks like. Is there a more famous literary novel by a living author at the moment? Harry Potter is probably still better known than Offred, but not many other characters.

I came to this fresh, or as fresh as is possible these days. This is my first read of the book. I haven't seen the television show or the movie. Or the opera for that matter. (There is one, it seems.) But twenty years ago or so, I did see a play at Toronto's Fringe Festival, and I thought, hey, that's The Handmaid's Tale, even though they weren't advertising as it as such, or even as an adaptation. I wondered if they'd gotten the proper rights. (Well, it was the Fringe Festival, so probably not.)

And the play was closely related to The Handmaid's Tale. I can say that now for sure. But I can't tell you why I knew what was the world of the novel even back then, but I did and I was right.

You don't have to have read Doyle, or seen a movie or a television show, or even a mouse in a deerstalker, to know who Sherlock Holmes is. The Handmaid's Tale is getting up to that level of mythic presence.

That all may explain a bit why, though it's been on the shelves here for a while, I haven't read it, but that was a mistake. I felt I knew the book, but there's still a lot there even if you know about the dystopia.

It's also a well (and interestingly) told story. The prose is impressive. The way information is doled out is very well-handled. There's tension and suspense; this world is terrifying, and bad possibilities could occur with any action. But still Offred has to act, and try, as best she can, to live.

And the politics are a little subtler than I suspected. In the end, though some people benefit, nobody really likes this world they've constructed. Not the Commanders, not the Wives, not the Handmaids, not the Marthas, not the Jezebels or the Econowives. But some of them meant well to begin with. The road to Hell really is paved with good intentions.

Anyway, you probably don't need me to tell you, but read it. Do.

Thursday, November 29, 2018

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Nonfiction November - What I learned (or Yikes! More books to read...)

The prompt for the last week of Nonfiction November comes from Katie at Doing Dewey and asks what new books have we added to our TBR list. This is the funnest prompt yet, and I've been so much enjoying going through all the lists that people have assembled.

So here's what particularly caught my eye:

Brona's Books

Bill Bryson/Notes From A Small Island -

I've been interested in Bryson for a while, but didn't know which one to read. Now I do!Buried In Print

Michael Dirda/Browsings -

I'd heard of this but I'd forgotten to write it down. It sounds very cool. Though actually I came across it at Words and PeaceDoing Dewey

Robertson Davies/A Voice From The Attic -

I read a different collection of Davies' essays once & really liked it. I'd never heard of this and it sounds great.Emerald City Book Review

Marie-Louise von Franz/Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales -

I'd never heard of her. This sounds fascinating.Head Full Of Books

Albert Marrin/Very, Very, Very Dreadful: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 -

This fits in with my other WWI reading. And that title!Anna Crowley Redding/Google It: A History of Google -

I saw Anne had this on her list and it looked good, so I immediately ordered it from my library. Then in the end she didn't like it much, but I've got it here now anyway...Howling Frog

Simon Winder/Danubia

the Hapsburgs! For me, that's enough said.Christopher de Hamel/Meetings With Remarkable Manuscripts -

about medieval manuscripts. The Other Reader is the medievalist in the house, but I'm the one interested in manuscripts.Nancy LN:

Imani Perry/Looking for Lorraine -

about Lorraine Hansberry, the playwrightJ. Blank/James Wright: A Life in Poetry -

but her post made me want to read more James Wright, too, and probably first...The Lusiads -

Classic about Portuguese explorersCarlo Levi/Christ Stopped at Eboli -

I knew of this and even own a copy, but it moved up about a million places on my TBR. (And yes, my TBR list probably is that long...)Quaint and Curious Volumes

Virginia Woolf/The Common Reader -

I read the first series years ago. This reminded I need to reread it and read the second series as well. I really don't know why I've waited so long.Quentin Bell/Virginia Woolf, A Biography

Michael Witworth/Authors in Context: Virginia Woolf -

Actually all of her Virginia Woolf selections look great.Readerbuzz

Lawrence Wright/God Save Texas -

addressing the increasingly remote Texan in me.Isabel Wilkerson/The Warmth of Other Suns -

I knew of this but needed reminding. Migration from the South to Chicago, for instanceAnd a whole list of great-looking books for writers on writing. The ones I've read (Zinsser, Dillard, Rilke) made me want to read the ones I hadn't. And made me reread Rollo May's The Courage to Create.

Thanks to all our hosts and particularly Doing Dewey for this week. And thanks to all participants for giving me all these new books to read!

Tuesday, November 27, 2018

Classics Club Spin #19. And the winner is...

That means it's Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison for me. That was the shortest on my chunkster spin list so I'm either disappointed or relieved or both.

It'll be my second Toni Morrison. I read Beloved some years ago, which I thought great, but the prose is a bit challenging.

Thursday, November 22, 2018

Rollo May's The Courage To Create

"This brings us to the most important courage of all. Whereas moral courage is the righting of wrongs, creative courage, in contrast, is the discovering of new forms, new symbols, new patterns on which a new society can be built."Rollo May is one of a group of psychologists and psychotherapists writing in the post-WWII period who are usually called humanist or existentialist. Mostly they worked in the U.S. Victor Frankl, Erich Fromm, Irving Yalom, Abraham Maslow.

May in this book (1975) says the usual psychotherapeutic observations on creativity are inadequate and often plain wrong. He's particularly hard on the "compensatory theory of creativity," that we create art to compensate for our inadequacies.

Instead he wants to inaugurate a new approach to the subject; he emphasizes the challenge of the process, the (at least occasional) joy in the result, and what's involved in getting there, particularly the alternation of productive and fallow periods.

"It is necessary that the artist have this sense of timing, that he or she respect these periods of receptivity as part of the mystery of creativity and creation."May himself was an amateur painter, and many of his examples are drawn from painting and sculpture, Picasso, Mondrian and Giacometti; but others are from literature: Joyce, Auden, Yeats, Dylan Thomas, Beckett, Camus and Stanley Kunitz are all cited. I found it fascinating, and a much more positive view of creativity than is usual in psychology. Maybe Maslow is as good, but he's less specific to the work of artists.

It is a book of its era, however, and not just that crazy 1970s cover on my edition. The Maharishi, TM, Gestalt all get their nod in one section. He talks about rebels, as not just someone who "takes over the dean's office."

He's also operating in the Freudian tradition. His main influences seem to be Adler and Rank; he also cites Jung. He is a bit subject to the casual misogyny in that tradition, or maybe it's still the era, though by 1975 he could have been a bit more woke. He casually cites a study of "artists and their wives;" there are a few other examples. Though to his credit he does use "he or she" on occasion, as above.

It's based on various lectures he gave; it more peters out than ends.

But with all that said, I still think the core of the book is fascinating and helpful on the subject and I've read it now a couple of times. I picked it up again after reading Deb Nance's list of books on writing here. (I tried to comment on her website, but my comment went AWOL...) I'd recommend it.

And now I learn from Wikipedia his middle name is Reese! I approve!

D. Reese Warner

Wednesday, November 21, 2018

Classics Club Spin #19

It's spin time again at the Classics Club, but this spin is especially twisty...we've got two months and a bit to read the book, and the challenge is to put those chunksters on the spin list. Dangerous! So here they are, starting with the relatively slim and graduating to the truly monumental books out of what remains on my classics club list.

1.) Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon

2.) Willa Cather's One of Ours

3.) Malcolm Lowry's Under the Volcano

4.) Edith Wharton's The Custom of the Country

5.) Hermann Broch's The Death of Virgil

6.) Samuel Butler's The Way of All Flesh

7.) Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship

8.) William Faulkner's Light In August

9.) Honoré de Balzac's Cousin Bette

10.) Walter Scott's Count Robert of Paris

11.) Henryk Sienkewicz' Quo Vadis

12.) Henry James' The Wings of the Dove

13.) Edmund Wilson's Patriotic Gore

14.) Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron

15.) John Galsworthy's The Forsyte Saga

16.) Bertrand Russell's A History of Western Philosophy

17.) Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene

18.) Plutarch's Lives

19.) Edmund Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

20.) The 1001 Nights

That goes from a mere 350 pages to a three volume monster at almost 4000 pages. Yikes. I don't know. Am I rooting for a low number or a high number? Should I get those Arabian Nights out of the way? What number would you pick for me?

And the winner is...#1. Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon.

Tuesday, November 20, 2018

Nonfiction November - Reads like fiction

For the fourth week of Nonfiction November, Rennie at What's Nonfiction? asks about nonfiction that reads like fiction:

Nonfiction books often get praised for how they stack up to fiction. Does it matter to you whether nonfiction reads like a novel? If it does, what gives it that fiction-like feeling? Does it depend on the topic, the writing, the use of certain literary elements and techniques? What are your favorite nonfiction recommendations that read like fiction? And if your nonfiction picks could never be mistaken for novels, what do you love about the differences?I'd say for me it's great if a volume of nonfiction reads like fiction when it's a topic area where it works. I'd say the best work of nonfiction I've read this year is Frederick Douglass' Narrative of the Life, the first version of his autobiography, and quite a lot of that did read like fiction and fiction of the best sort. The story quite naturally has narrative drive: it goes from his birth and earliest memories, from one owner to another, bad and worse, how he learns the forbidden activities of reading and writing, and ends with the climax of his escape to freedom. The prose is quite punchy, rather surprisingly so for something that came out in 1845.

But the best other nonfiction works I read this year definitely do not read like fiction, and that's OK, too. Earlier in the year I read Brian Dillon's volume Essayism, which is a series of essays about his favorite essayists intermixed with biographical elements. I wouldn't want this to read like fiction, and it has no need to. And just this month I read Raymond Geuss' Changing The Subject, Philosophy from Socrates to Adorno, which was an idiosyncratic history of philosophy with footnotes and a reasonably full academic apparatus, but I still found it a great read. (I may have skipped some of the footnotes, though.)

So I guess my answer is, it depends!

But in thinking about the subject I got to browsing and reminded myself about these two travel books, which definitely read like great adventure novels, traveling in Arabia in the 30s and 40s:

Wilfred Thesiger's Arabian Sands

Freya Starks' The Southern Gates of Arabia

Sunday, November 18, 2018

Ronald Bates' The Wandering World (#CanBookChallenge)

|

| Something slim and serious. And then there's Humpty. |

Clinging to its inescapable fall,

Descending with a finality of care,

Limning the trees and house-fronts. All

Whiteness is soft and warm:

There is no sharp harm.

That's the opening from Ronald Bates' "The Fall of Seasons" in his volume of poetry The Wandering World. Maybe only a Canadian poet would begin a four-sectioned poem on the seasons with praise of winter. If I had taken a picture of the book on Friday it could have matched the poem, but our Toronto snowfall from then is pretty much melted now, at least where I'm located. But that very nicely describes my sense of a first snow.

The book was Bates' first volume of poetry and came out in 1959 with MacMillan of Canada when he was 35. At that point he had taught at the University of Uppsala in Sweden, but had returned to Canada and was teaching at the University of Western Ontario. A second volume of poetry came out in 1968 with a privately printed volume between the two. His academic writing covered authors from James Joyce to Northrop Frye. (Details from a brief biography here.)

Without being rigorously formal, the poetry is fairly traditional for 1959, I'd say; the above lines are representative, with a distinct iambic beat. The line length varies here and elsewhere, but this is unusual in the patterned use of rhyme; other poems also use it, but most don't.

The book is sixty pages, divided into sections: Histories, Myths, Interiors, Landscapes, and Constructions. I was most taken with Myths and Landscapes. Here's the opening of 'Dedalus' from Myths (the only satirical poem in the collection):

The point is, he did not fly at all.

All those rumours about a fall

Were spread to bring me into disrepute.

A fatal accident's poor advertising

So it's not at all surprising

To find my trade's fallen off to some extent.

Bates seems mostly lost at this point, I'm afraid. I bought the book on a flyer when my local used bookstore was having a sale recently. I thought it looked interesting enough to read, and I did read it. Googling I found a contemporaneous review in the first issue of the journal Canadian Literature that mostly praised Irving Layton and dismissed Bates in a few lines. Unfairly, I'd say. There's things in the book worth reading.

My volume had this written on the flyleaf: "...in the meantime, poetry."

An entry in the Canadian Book Challenge:

Thursday, November 15, 2018

Raymond Geuss' Changing the Subject: Philosophy from Socrates to Adorno (#NonFicNov)

I'd like to be a better reader of philosophy than I am, but it's a hard subject. One of the ways I think I might improve is by reading histories of the subject, and the very title of Raymond Geuss' new book Changing the Subject: Philosophy from Socrates to Adorno suggested it might fit the bill.

The review I read of the book did mention that the volume was idiosyncratic in its approach and would better reflect Raymond Geuss than all of philosophy and that's true. So I'm still looking for that good history of philosophy to ground my readings. (Suggestions in the comments greatly appreciated!)

But I thought this was very good. Geuss writes in the introduction to his book:

The philosophers he discusses are Socrates, Plato, Lucretius, Augustine, Montaigne, Hobbes, Hegel, Nietzsche, Lukács, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and Adorno. He generally picks one work from each author and addresses the question that work covers. He's good at it. While there may be more to Heidegger than is covered in fifteen pages, that he can say anything about about Being and Time and have it sound correct and make sense impressed the heck out of me. And he's equally good on most of the authors.

The works Geuss chooses revolve around a theme, which I would describe as, the question of how to live as an individual in society. He's an emeritus professor at Cambridge; I've read nothing else by him, but that's a big enough theme to have occupied an entire career, and may have done so for him.

And he can be funny! in a philosophical kind of way...

The review I read of the book did mention that the volume was idiosyncratic in its approach and would better reflect Raymond Geuss than all of philosophy and that's true. So I'm still looking for that good history of philosophy to ground my readings. (Suggestions in the comments greatly appreciated!)

But I thought this was very good. Geuss writes in the introduction to his book:

...its ideal reader would be the intelligent person with no special training in academic philosophy who thinks that philosophers have sometimes raised some interesting questions and who wishes to try to get clear about whether this is the case and what some of these questions might have been, in the interest of thinking about them further.I thought, hey that's me! And he really does write successfully for such a person.

The philosophers he discusses are Socrates, Plato, Lucretius, Augustine, Montaigne, Hobbes, Hegel, Nietzsche, Lukács, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and Adorno. He generally picks one work from each author and addresses the question that work covers. He's good at it. While there may be more to Heidegger than is covered in fifteen pages, that he can say anything about about Being and Time and have it sound correct and make sense impressed the heck out of me. And he's equally good on most of the authors.

The works Geuss chooses revolve around a theme, which I would describe as, the question of how to live as an individual in society. He's an emeritus professor at Cambridge; I've read nothing else by him, but that's a big enough theme to have occupied an entire career, and may have done so for him.

And he can be funny! in a philosophical kind of way...

Socratic irony and the Socratic mode of questioning were monumentally inventive ways of being irritating.Recommended.

Wednesday, November 14, 2018

Nonfiction November - (Be)come(ing) the Expert: WWI anti-militarism

It's the third week of Nonfiction November and the prompt from JulzReads (thanks for hosting!) challenges us to be or become or ask an expert on a topic of interest.

Well, I'm pretty much incapable of thinking that I could be an expert on anything, but maybe I could become one? By asking? Seems like expertise is always a process of becoming.

Anywho, I've been curious about the opening of World War I. The centennial of that event wasn't so long ago, and there have been a number of books on the subject in the last couple of years. There was considerable enthusiasm at the start of the war, and if the so-called 'August Madness', the moment where everyone wanted war, is sometimes overstated, it was a significant phenomenon. How could anybody have wanted it? To us now, it seems like such a bad idea. But even odd, intellectual ducks, like Hesse, Wittgenstein, Kafka (thanks @magistrabeck!) were desperate to go fight.

Mass enthusiasm for bad ideas in public policy is just a thing that worries me these days. I don't know why...

But some intellectuals and thought leaders resisted the enthusiasm, or at least wanted the war to be prosecuted without demonizing the enemy. Romain Rolland, Lytton Strachey, George Bernard Shaw, Hermann Hesse (after a little bit).

Some books on the topic:

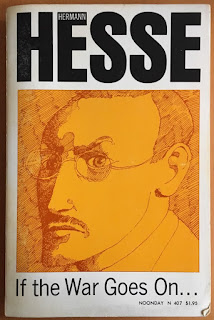

Hermann Hesse's If The War Goes On...

Romain Rolland's Above The Battle (Project Gutenberg has it here)

George Bernard Shaw's Common Sense About The War (here)

Michael Holroyd's Lytton Strachey: The New Biography. The Other Reader gave me this after we saw the movie years ago.

I also really liked the Teaching Company course on WWI. The August Madness lecture early on addresses these issues.

And another way to resist the militarism of the war...

Any other books on the resistance to World War I in the early days? Let me know!

Saturday, November 10, 2018

Christopher Hibbert's The House of Medici: Its Rise and Fall (#NonficNov)

I thought I'd read up on the history of the Medici and Florence after reading George Eliot's Romola a couple months ago; I put in a hold request at the library; it arrived only recently. It could have been a fiction/nonfiction pairing; that was my idea even before the pairing idea showed up as a theme for #NonficNov, but in fact it wasn't as strong an entry as I had hoped.

That's not the fault of the book, which was good.

But Romola mostly takes place during the years when the Dominican priest Savonarola was guiding the restored Florentine republic, and the Medici were in exile. It's glossed over pretty quickly in Hibbert.

I find the history of Italy pre-unification hard: too many city states, too many aristocratic families vying for power in those city states, and then when some aristocrat becomes pope, there's a new name, but it matters very much that Julius II, for example, was of the della Rovere family.

Hibbert, not an academic, but a professional popular historian with a deep interest in Italy, tells his story well and readably. I'll probably have forgotten most of the details six months from now, but that says more about me than the book. After a brief bit of prehistory, it runs from the birth of the first famous Medici, Cosimo, in 1389 to the death of the last, Anna Maria, in 1743. The greatest emphasis on the years of Cosimo, Lorenzo the Magnificent and the first Medici pope, Leo X.

One thing I can tell you I will remember is that a surprising number of the Medicis were fat. All that rich living, I guess.

I'd recommend the book if you're interested in the topic, and especially if you're traveling to Florence; it's very strong on associating the sites where the events occurred with what's actually on the ground in Florence today.

That's not the fault of the book, which was good.

But Romola mostly takes place during the years when the Dominican priest Savonarola was guiding the restored Florentine republic, and the Medici were in exile. It's glossed over pretty quickly in Hibbert.

I find the history of Italy pre-unification hard: too many city states, too many aristocratic families vying for power in those city states, and then when some aristocrat becomes pope, there's a new name, but it matters very much that Julius II, for example, was of the della Rovere family.

Hibbert, not an academic, but a professional popular historian with a deep interest in Italy, tells his story well and readably. I'll probably have forgotten most of the details six months from now, but that says more about me than the book. After a brief bit of prehistory, it runs from the birth of the first famous Medici, Cosimo, in 1389 to the death of the last, Anna Maria, in 1743. The greatest emphasis on the years of Cosimo, Lorenzo the Magnificent and the first Medici pope, Leo X.

One thing I can tell you I will remember is that a surprising number of the Medicis were fat. All that rich living, I guess.

I'd recommend the book if you're interested in the topic, and especially if you're traveling to Florence; it's very strong on associating the sites where the events occurred with what's actually on the ground in Florence today.

Friday, November 9, 2018

Hermann Hesse's If The War Goes On... (#NonficNov)

The majority of the essays are from the time of World War I and the immediate aftermath; Hesse's thought changes profoundly at the time, as was true of many. The first essay takes it title from the beginning of the Ode to Joy section of Beethoven's Ninth, "O Freunde, nicht diese Töne." O friends, not these sounds. Beethoven turns to the exhilaration of Schiller's Ode To Joy; Hesse just asks that his fellow intellectuals not spew hatred of their enemy, that if a war must be fought, it can be done without contempt for those whom just six months ago you admired. This essay, which appeared in the Zurich newspaper, and not in Hesse's homeland of Germany, spurred Rolland to write to Hesse. The opening essays of Rolland's Above The Battle try to make the same point.

Well. A difficult proposition. Not the least risk of war is its need to dehumanize the enemy.

The next several essays document Hesse's growing disenchantment with the war. But it's the essays of 1919 I found especially interesting, the key one being "Zarathustra's Return." As you might guess, Nietzsche is the central influence here. But what Hesse gets from Nietzsche is not what you might expect, and certainly not what Nietzsche's sister and her fellow Nazis would have wanted you to get. Rather Hesse draws from Nietzsche's insistence that we not succumb to herd mentality the idea we should be pacifist, that we should withdraw from society; if society wants the individual to follow blindly into mass mobilization, then perhaps a Nietzschean refusal leads to pacifism.

Years ago now when I read those novels of Hesse I did read, I was put off a bit by the implied argument of many of them, that we disengage from the world; the Glass Bead Game was my favorite at the time for what were philosophical reasons, the fact that Knecht leaves the academy to once again engage with the world at the end. Hesse withdrew from the world to live on his Swiss mountain, and his books often argue that philosophy. But reading this made that decision, for me, if not defensible, at least understandable.

The last few essays were less interesting and are mostly around the period of World War II. It also includes his brief Message to the Nobel Prize Banquet of 1946.

A fascinating book, and crucial to understanding Hesse's novels, I think, and to the post World War I mindset.

Labels:

Hermann Hesse,

NobelLaureate,

NonFic2018,

Rolland,

TBR

Monday, November 5, 2018

Nonfiction November: Fiction and Nonfiction Pairing

It's the second week of Nonfiction November and Sarah (thanks for co-hosting!) of Sarah's Bookshelves challenges us to match up nonfiction reading with fiction reading. I've got two that have been in my mind for a while, one for a very long time.

Steinbeck On How To Write A Novel (with Novel)

|

| Humpty, meet John; John, meet Humpty |

I read East of Eden years ago, though I've seen the movie more recently; it's one of the great Steinbeck novels, even if I find Cathy Ames just a wee bit too monstrous. ("Bad divorce, John?" "Humpty, let me tell you! Grumble, grumble...") But the idea is to read them both together.

And Now I'm Ready At Last...

|

| Humpty had a great Fall (or at least Nonfiction November) |

Years ago I started reading Edmund Wilson's Axel's Castle (literary criticism about Joyce, Proust, Eliot, Yeats, Valery, and Gertrude Stein published in 1931) and I thought (at the time) this is hopeless! I haven't read any of these books. Generally I like Wilson's nonfiction, especially To The Finland Station.

Well, I had probably read Eliot's Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats by then, which is hiding in there between Yeats and Proust. But still.

Now, it's years later, and while I'm sure there are still books discussed in Axel's Castle I haven't read, I'm kind of hoping I'm close enough to make sense of the book. In any case I put it on my Classics Club list.

Finnegans Wake (in the picture) is still Unnamed Work In Progress at the time of Axel's Castle. Wilson managed to score a couple of passages and quoted them at the end of his book, but fortunately won't be discussing that particular still-for-me unreadable volume of Joyce.

Missing from the picture is Gertrude Stein. I don't know where she's hiding...shy, I guess...

Looking forward to other great pairings. Happy Nonfiction November!

Sunday, November 4, 2018

Cora Siré's Behold Things Beautiful (#CanBookChallenge)

Alma Álvarez left Luscano in 1991; she had been rounded up with other 'subversives,' i.e., college students and intellectuals, and held in the notorious La Cuarenta prison; she was tortured there; she narrowly escaped becoming another one of Luscano's los desaparecidos. The junta in Luscano fell in 1995, but there's been no reckoning. It's now 2003, Alma is living in Montreal, teaching Spanish literature to undergraduates, and trying to forget. But her mother back home is dying, and her friend Flaco arranges for Alma to give a talk on her field of expertise at the university in Luscano. Alma's feelings about returning home are complex to say the least.

If you haven't heard of Luscano, don't worry, you're not meant to; Cora Siré made up the country, like Ruritania, Orsinia, or most particularly the Costaguana of Conrad's Nostromo. It's nestled in somewhere between Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay.

Like Nostromo, the novel blends the personal and the political in a small society; and, while it doesn't have the boys' own adventure quality of Nostromo, there is tension and danger. The psychological after-effects of torture feature in both novels. Flaco has more in mind that just giving Alma an opportunity to see her mother. Retribution and protest is in the air and Alma feels her life threatened, not unreasonably. There's also the possibility of romance; Alma (and others) have had their emotional life curtailed, damaged by the terrors of the junta in the early 90s. Can they trust again?

I thought it a very strong novel. It made me want to reread Conrad, and possibly Vassilikos' Z or Puig' Kiss of the Spider Woman, the better to place it in their company.

I did have an issue, though. It's clear that Siré is very interested in the poetry of Delmira Agustini. Agustini--I'd never heard of her--is a real Uruguayan poet, born in 1886 and dead in 1914, murdered (by her estranged husband) probably, though possibly as part of a dual suicide. The title, Behold Things Beautiful, comes from a poem of Agustini's:

But still. Agustini's an interesting enough find, and the novel as a whole is powerful.

The novel ends ambiguously, uncertainly, with the possibilities of both hope and new dangers. Correctly, I thought.

If you haven't heard of Luscano, don't worry, you're not meant to; Cora Siré made up the country, like Ruritania, Orsinia, or most particularly the Costaguana of Conrad's Nostromo. It's nestled in somewhere between Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay.

Like Nostromo, the novel blends the personal and the political in a small society; and, while it doesn't have the boys' own adventure quality of Nostromo, there is tension and danger. The psychological after-effects of torture feature in both novels. Flaco has more in mind that just giving Alma an opportunity to see her mother. Retribution and protest is in the air and Alma feels her life threatened, not unreasonably. There's also the possibility of romance; Alma (and others) have had their emotional life curtailed, damaged by the terrors of the junta in the early 90s. Can they trust again?

I thought it a very strong novel. It made me want to reread Conrad, and possibly Vassilikos' Z or Puig' Kiss of the Spider Woman, the better to place it in their company.

I did have an issue, though. It's clear that Siré is very interested in the poetry of Delmira Agustini. Agustini--I'd never heard of her--is a real Uruguayan poet, born in 1886 and dead in 1914, murdered (by her estranged husband) probably, though possibly as part of a dual suicide. The title, Behold Things Beautiful, comes from a poem of Agustini's:

Turn out the lights and behold things beautiful;Agustini is Alma's field of expertise, the reason she returns to Luscano. As such, she's the McGuffin that sets the story in motion, and can't be disposed of entirely. But she occupies an indeterminate place in the novel. She's treated at too much length to be just a McGuffin, but Agustini's themes are insufficiently integrated into the novel as a whole to warrant the space given to her. I wanted either more or less, and I can't say which of those would have been correct: I just felt the way it was wasn't quite right.

Close all doors and enter illusion;

Uproot from mystery a handful of stars

And cover with flowers, like a triumphal vase, your heart...

But still. Agustini's an interesting enough find, and the novel as a whole is powerful.

The novel ends ambiguously, uncertainly, with the possibilities of both hope and new dangers. Correctly, I thought.

Labels:

CanLit,

Cora Sire,

Signature-Editions,

Smallpress,

TorontoPublicLibrary

Thursday, November 1, 2018

#RIPXIII: Oscar Wilde's The Portrait of Dorian Gray

|

| Hubert contemplates having his portrait painted |

Well, we were in high school. We probably thought it actually meant something that this was 'Oscar Wilde's most famous novel' as it proclaims on the cover of the edition we used. Yes... As the Other Reader wondered, is it even grammatical to use the superlative when there's only one object?

The scribblings in my high school edition tell me that Mr. Wall pushed hard on the psychosexual interpretation of Dorian Gray. That doesn't surprise me, even now. Later in the year, we read Peter Shaffer's Equus, which may be good on stage, but even in high school I recognized Equus as the most unimaginatively unsubtle portrayal of mother-fixation imaginable. Oh, hey, Dr. Freud! And my marginal notes in this suggest that Dorian Gray was interested in Sibyl Vane because his mother married beneath her. Thank you, Mr. Wall, for your (rather expected) opinion.

One of the reasons I reread this now, after years, was Adam's fascinating series of posts at Roof Beam Reader covering five different theoretical approaches to Dorian Gray. And, of course, the psychosexual isn't all wrong. But there are definitely others and Adam gives a great overview.

However, what struck me most was how many of the great Wilde lines come from this. Wilde is famous for cynical, paradoxical, witty epigrams. They float free of context and could appear almost anywhere. I somehow had it in my head that all these came from the plays, but they're spoken by Lord Henry Wotton in Dorian Gray:

"When her third husband died, her hair turned quite gold from grief."

"To get back my youth I would do anything in the world, except take exercise, get up early, or be respectable."

"...for there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about."

"...and as for believing things, I can believe anything, provided that it is quite unbelievable."I had also decided to reread this now for Readers Imbibing Peril; it is, at heart, a gothic novel, with murder, disposal of the body, opium-taking, a Romantic view of the past, and above all, a bargain with the devil, the exchange of one's soul for eternal youth and beauty. But a laugh-out-loud gothic novel filled with one-liners? Only Oscar Wilde.

It is now just after midnight my time, so I'm a little late for RIPXIII. I'm blaming it on the Batmans and Luna Lovegoods and Fairy Godmothers that kept coming to my door earlier tonight...

Labels:

1000_books,

Aphorisms,

Oscar Wilde,

Reread,

RIPXIII

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)